Want to Test Water or Soil? Your Smartphone’s got the Answer

Researchers have invented a way to use a mobile device to detect common ionic contaminants in samples dropped onto its screen.

August 24, 2021

Most of us use the touchscreen of our mobile devices to communicate with friends or navigate our favorite app. But new research has invented a way to use touchscreens as a sensor for detecting contaminants in soil or drinking water quickly and easily when another technology is not available.

Scientists from the University of Cambridge have demonstrated a proof of concept for dropping liquid soil or water samples on common smartphone screens that can then identify common ionic contaminants in the sample.

The team—led by professors Ronan Daly from Cambridge’s Institute of Manufacturing and Lisa Day from Cambridge’s Department of Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology—said that the sensitivity of the touchscreen sensor in this novel use is comparable to typical lab-based equipment, which would make it a useful tool in remote places or low-resource settings.

While other research has devised ways to use a smartphone for sensing applications, typically they have relied on the device’s camera or required the use of a peripheral device or significant screen changes to function.

The Cambridge team wanted to see if they could “interact with the technology differently, without having to fundamentally change the screen,” said Professor Ronan Daly from Cambridge’s Institute of Manufacturing, who co-led the research.

“Instead of interpreting a signal from your finger, what if we could get a touchscreen to read electrolytes since these ions also interact with the electric fields?” he said in a press statement.

Turning the Screen into a Sensor

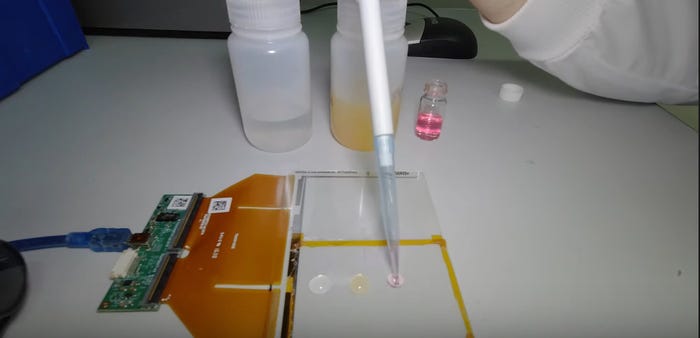

To come up with their solution, the team started by using computer simulations to see if their idea would work and then used a standalone touchscreen similar to those used in smartphones and tablets to test it.

Researchers dropped various liquids onto the screen to measure a change in capacitance—or the ratio of the amount of stored electric charge stored to a difference in electric potential. Smartphone screens are covered in a grid of electrodes; they function because someone’s finger disrupts the local electric field of those electrodes, and the phone interprets the signal.

The team then recorded the measurements from each droplet using the standard touchscreen-testing software. Ions in the fluids interact with the screen's electric fields differently depending on the concentration of ions and their charge, researchers observed.

In their experiments, researchers discovered a linear trend for a range of electrolytes measured on the touchscreen, with the sensor saturating at an anion concentration of around 500 micromolar, they said. This measurement can be correlated to the conductivity measured alongside, a detection window ideal to sense ionic contamination in drinking water, researchers noted.

One early application for the technology, then, could be to detect arsenic contamination in drinking water, they said. Arsenic is a common contaminant found in groundwater globally, though municipal water systems detect it and filter it out before it gets to the water supply delivered to people’s taps at home.

However, in places without water-treatment plants, arsenic contamination in water is a major health problem, making a solution that lets someone place a drop of water on a smartphone to test it a valuable proposition, researchers said.

Sensing Optimization

Researchers published a paper on their work in the journal Sensors and Actuators B. They also have published a video on YouTube showing how the technology works.

While the current sensitivity of phone and tablet screens are tuned for fingers, this could be modified by changing the electrode design for sensing optimization to make the droplet test more effective.

“The phone’s software would need to communicate with that part of the screen to deliver the optimum electric field and be more sensitive for the target ion, but this is achievable,” research co-leader Hall said in a statement.

The team plans to continue their work to find ways to use the screen to detect a wider range of molecules, which paves the way for numerous potential health and other applications, she added.

“This is a starting point for a broader exploration of the use of touchscreen sensing in mobile technologies and the creation of tools that are accessible to everyone, allowing rapid measurements and communication of data,” Hall said in a statement.

Elizabeth Montalbano is a freelance writer who has written about technology and culture for more than 20 years. She has lived and worked as a professional journalist in Phoenix, San Francisco, and New York City. In her free time, she enjoys surfing, traveling, music, yoga, and cooking. She currently resides in a village on the southwest coast of Portugal.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like