Mazda engineers figured out how to use the MX-5 Miata’s suspension geometry to control body roll in corners.

Engineers are at their best when they are contriving unorthodox solutions to everyday problems. Mazda’s engineers came up with such a solution that uses the inherent geometry of the MX-5 Miata’s rear suspension as it swings through its range of motion to control body roll in corners.

Cornering, after all, is the Miata’s calling card, so it is important for the car to do this well. Much effort went into refining the car’s steering, its suspension geometry, the valving of its dampers, the thickness of its anti-roll bars, and the hardness of the various rubber bushings used throughout, ensuring the best possible response when the road gets twisty.

And it seemed good enough to most of us. But not to Mazda’s engineers, who wanted still better control of body roll. But they didn’t want to muck up any of these other ingredients while addressing the issue. Instead, they chose to apply some intelligence to repurpose the inherent characteristics of the car’s rear suspension.

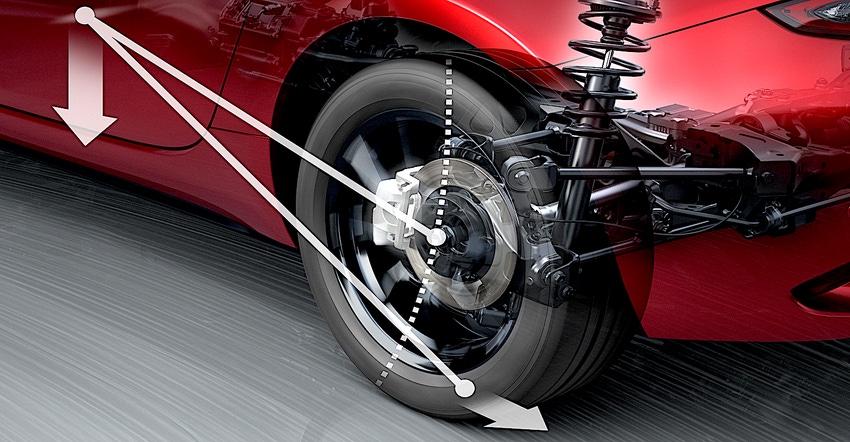

It works by recognizing that the rear suspension control arms swing rearward as they move upward when the suspension compresses. The converse of this is that when the suspension moves rearward, as it does under braking, it also moves upward.

Mazda’s insight was to apply a minuscule amount of brake force to the inside rear wheel when cornering, lifting that wheel up to keep the body flatter in the curve. The system, which Mazda calls Kinematic Posture Control, works automatically and invisibly, explained chief engineer Dave Coleman.

Because there is no “off” switch for the system, drivers can’t A/B test the car with and without it working, but Mazda did plenty of testing to confirm the benefits, he said. It makes turn-in more linear and precise, so the car goes exactly where you want it to go the first time.”

Although KPC is purely a software solution acting on the existing brake system, its invisibility lets it feel like a mechanical solution, like a limited-slip differential or another hardware component, Coleman said. That kind of natural, uncomplicated response is Mazda’s aim for all of its vehicles, but most especially so for the Miata, he added.

“It is only responding to the difference in wheel speed between the two rear wheels,” he said, making it behave like a mechanical system as a property of the vehicle without any input by the driver.”

The brake drag applied is equivalent to the drivetrain drag of the air conditioning compressor engaging, so it is not enough to induce torque vectoring or to cause noticeable forward weight transfer, according to Coleman. “I feel the car just goes directly where I want to point it,” he said “When you are on a twisty mountain road the impact [of KPC] is quite obvious.”

To gauge that impact, Mazda benchmarked Miatas in all of the various configurations. “The incremental improvement on the tight twisty road was as big as going from the base dampers to the Bilstein dampers,” Coleman noted. “It worked even better than we thought it would.”

That has to be the happy ending engineers seek when they launch a new project, especially when it is a simple one that only adds some software to existing hardware.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like