Want Creative, Sustainable 3D Printing? How About Seaweed-Based Bioink

ArtSea Ink gives artists a colorful new alternative to typical polymer materials for developing artwork using the medium.

August 17, 2021

Researchers have developed colorful, algae-based inks for 3D printing called ArtSea Ink that gives artists a bioink alternative to using the medium more for creative designs and artwork.

A team of scientists at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) developed an ink comprised of mica pigments in alginate, a sugar from seaweed that forms a stable gel without heat. While the ink does not remain in its stable form over time, it biodegrades quickly so the resulting object does not create any harmful waste.

Recognizing that artists are beginning to use the 3D printing medium as a new means for creating compositions now that it’s evolved, the team, led by PNNL researcher Anne Arnold, aimed to develop an alternative to polymer-based inks typically used, and the high heat required to solidify them into a finished form, researchers said. They also wanted ink that could print in different colors.

“Development and focus on the use of 3DP for the arts have been based primarily on the use of synthetic, petrochemical-derived, polymer (e.g., thermoplastic) feedstocks,” researchers wrote in a paper on their work published in the journal ACS Omega. “These thermoplastic feedstocks often necessitate processing with heat or UV light and, therefore, can require dedicated printing hardware to operate. In contrast, biologically derived polymers such as carbohydrates used to create bioinks—3D printable hydrogel matrices—often do not require heating the material for 3DP.”

However, while the use of bioinks and biologically derived polymers, in general, for 3DP is widespread, little attention has been given to using these materials as 3D printable artistic media.

Finding the Formula

Researchers already were familiar with both xanthan gum, another biologically derived polymer used as a binder and thickening agent in acrylic emulsion paints, and alginic acid, a cheap and widely used bioink for 3D printing.

“Alginate is a polysaccharide copolymer with a high molecular weight that, like xanthan, turns into a vicious gum when hydrated and a robust hydrogel when cross-linked with cations, such as [unbound calcium].”

Inspired by the similarity of the physicochemical properties of alginate and xanthan gum and the growing body of knowledge of alginate as a 3D printing bioink, researchers surmised that alginate could serve as a colorant binder, or a binding medium, and be used as “a new art medium with high processability.”

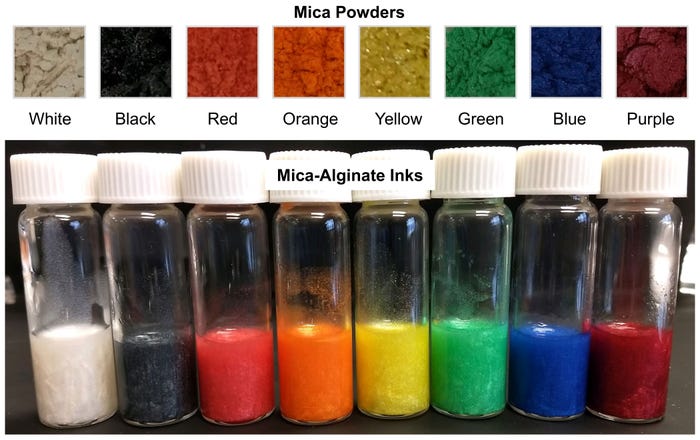

One thing about alginate, however, is that it is almost colorless. To give it the color needed to optimize the ink for art production, the team added mica powders to the alginate to create their ink, which can be used in both 2D and 3D compositions.

Creating the Bioink

To develop the ink, researchers prepared an 8 percent alginate solution in water and added one of eight different colors of mica pigments, which dispersed completely in the solutions to create vibrant, pearlescent colors, they said. They also found that they could control the consistency of the media by adding more or less the calcium chloride crosslinker.

The team demonstrated the new bioinks, which they call ArtSea Ink, by 3D printing two examples of art—one a 2D representation of a firefly, with a glow-in-the-dark additive to depict its abdomen, and the other was a 3D structure showing the human brain’s anatomy.

If kept in a neutral solution of calcium chloride, the 3D structures remained stable. However, right now any art created with the bioinks isn’t stable over the long term--which could be an advantage because the material, unlike plastic, will biodegrade quickly if discarded.

Elizabeth Montalbano is a freelance writer who has written about technology and culture for more than 20 years. She has lived and worked as a professional journalist in Phoenix, San Francisco, and New York City. In her free time, she enjoys surfing, traveling, music, yoga, and cooking. She currently resides in a village on the southwest coast of Portugal.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like