This Itty Bitty Device Could Find Ovarian Cancer Earlier

A University of Arizona researcher have developed a device small enough to image the fallopian tubes.

January 19, 2022

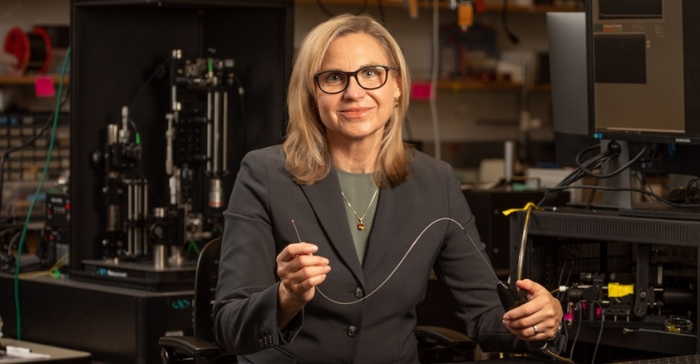

Jennifer Barton has spent years developing a device small enough to image the fallopian tubes and search for signs of early-stage ovarian cancer. Finally, the device has now been used in study participants for the first time, as part of a pilot human trial.

At 0.8 millimeters in diameter, the falloposcope's small size and high resolution are unprecedented.

"It's itty bitty," said Barton, director of the University of Arizona BIO5 Institute and Thomas R. Brown Distinguished Chair in biomedical engineering. "You just couldn't have fabricated something like this, even six, seven years ago."

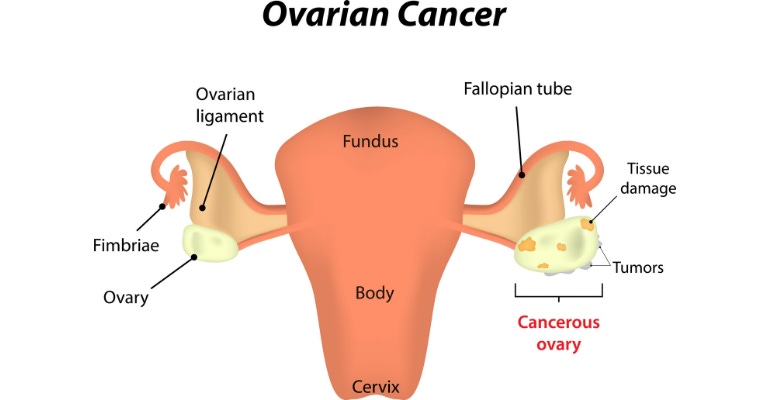

The device could go a long way toward helping doctors detect ovarian cancer earlier. Currently, fewer than half of all women with ovarian cancer survive more than five years after diagnosis because most cases are not found until the cancer is in an advanced stage, due to a lack of effective screening and diagnostic tools.

Barton, shown below with the falloposcope, holds appointments in optical sciences and medical imaging, and is a member of the UArizona Cancer Center.

Could the falloposcope detect ovarian cancer earlier?

For the pilot trial, John Heusinkveld, MD, is using the falloposcope device to image the fallopian tubes of volunteers who are already having their tubes removed for reasons other than cancer. This will allow researchers not only to test the effectiveness of the device, but also to start establishing a baseline range of what "normal" fallopian tubes should look like. Since September, Heusinkveld has successfully used the falloposcope in four volunteers.

FDA has labeled the study as having "non-significant risk," but testing the device on an organ that's about to be removed reduces the risk even more, the University of Arizona noted.

"This is the first endoscope that can fit inside a fallopian tube and actually see anything below the surface with high resolution," said Heusinkveld, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the College of Medicine in Tucson, AZ, and a board-certified specialist in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery in Banner – University Medical Center Tucson's department of obstetrics and gynecology. "We were very pleased with the images the device was able to capture in its first inpatient uses, and we look forward to gathering more data."

The American Cancer Society estimates that, in 2022, about 19,880 women in the United States will receive a diagnosis of ovarian cancer, and about 12,810 will die from the disease. Barton hopes her falloposcope will help save the lives of some women and vastly improve quality of life for others.

With early-stage detection, doctors could perform prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomies – removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes – before ovarian cancer spreads. Because researchers believe ovarian cancer usually starts in the fallopian tubes, many physicians recommend that women at risk for ovarian cancer have their ovaries and fallopian tubes removed. Many women opt for the surgery because of its potentially lifesaving benefits, but it isn't without drawbacks. The procedure thrusts women into surgically induced menopause, with side effects including hot flashes, mood swings, and a higher risk of heart and bone disease.

Barton cited one example of a study in which 122 patients who were known carriers of genes that increased their risk for cancer had their fallopian tubes removed as a precaution. Analysis of the tubes after removal showed that only seven of the women were in the process of developing ovarian cancer.

"This device could allow us to tell those other 115 women, 'Hey, you are perfectly normal, and we'll come back and check on you every couple of years to make sure everything is OK,” Barton said.

Regular falloposcope screenings could mean that even patients who do ultimately opt for the removal procedure could do it later in life – for example, after childbearing years.

"Anecdotally, I can tell you that when a patient has her ovaries removed at a young age – almost always for cancer risk reduction – she is placed on supplemental hormones, and a significant percentage of them come back and say, 'You know, I just don't feel as good as I did,'" Heusinkveld said. "And there's nothing you can do about that, aside from fiddling around with dosage. So, if we can delay removing ovaries until an age where they're truly inactive, that's going to be a pretty big health benefit."

Click here to read the full story, including the techniques Barton used to develop the device.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)