How to Build a Better Planting Operation

Spring planting is a highly automated process that involves putting 32,000 to 40,000 seeds per acre into the soil during a fully programmed operation.

February 12, 2021

Farming has advanced profoundly in recent years. Planting seeds in the spring is an operation that is as automated as any factory process. The tractor is often referred to as a robot, and the planting equipment is programmed to place each seed at a specific depth in the soil. The depth is determined by the condition of the soil on planting day.

We caught up with Than Hartsock, global director of corn & soy production systems at John Deere, to walk us through the process of building a fully automated agricultural planting operation.

Design News: What are the preparations that come before planting day?

Than Hartsock: You think about the planting season. In the Midwest, if you’re planting soy or corn, the planting season for putting the seeds into the ground is early-to-mid April. Leading up to that planting season, the farmer needs to make many decisions, such as what crop will be planted on which tract of land. Will you plant corn? Soybeans? These decisions are often made based on economics. Sometimes it’s based on last year’s results. Determining exactly when to start involves moisture and weather conditions.

DN: What considerations are involved before the planting begins?

Than Hartsock: The farmer will work with his network of agronomy consultants – maybe someone from the seed company or an independent agronomist. They decide what the target seed density and population is. What type of information does the agronomist use? They look at the data from smart machines from last year or the last five years.

Say you look at the last year. At the end of the year, the combine doing the harvesting measures the performance and the yield to see how much grain was produced. Then in the John Deere Operations Center desktop or mobile app, you can look at the performance rate and density. Then you can make the target.

Say you decide on the second week of April. The sun is shining. The equipment is ready. Some preparatory maintenance has been done on the equipment. The farmer has engaged the John Deere dealer to look at the hardware and software before everything is ready. Then the automation gets involved. The farmer uses the technology to make sure the right number of seeds will get planted in the right place.

DN: How is the field itself chosen?

Than Hartsock: The farmer decides what field to plant first. If you have 5000 acres to plant, that means 50 to 100 fields to work on. The farmer takes into account the different soil conditions. Which fields are fit to plant? They have to be not too wet and not too dry. You take samples of the soil and decide what field is first. The tractor or the robot is hooked up to the planter. The combination of those two machines will do the job of planting.

DN: How is the equipment programmed to plant the field?

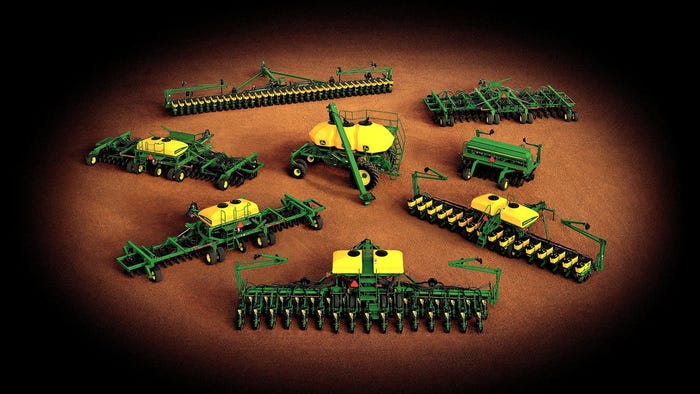

Than Hartsock: The machine is highly technical. It will drive itself with a one-inch error rate using GPS positioning. The planter is highly automated. It has a tremendous amount of technology. You can plant with a 60-foot wide, 24-row corn planter. There are 24 individual row units, and each unit has sensors and actuators that in real-time are controlling the downforce that is acting on the soil. The downforce determines the placement and depth of the seed.

The soil has to fit for germination. The depth is determined by actuators. You want to make sure you plant the right amount of seeds per acre. With corn, that’s between 32,000 and 40,000 seeds per acre. That’s a big span. The farmer decides on a particular goal between 32,000 and 40,000. The planter is equipped with electric drives to plant each seed. The speed is set to match the number of seeds getting planted, so regardless of the speed of the planter, the exact number of seeds are planted per acre.

DN: At this point is the planting operation automated?

Than Hartsock: As the machine plants, it’s highly automated. The tractor is driving itself. The planter knows the target rate and depth of the seed; it knows how hard to push the seed into the soil. The sensors monitor the job and report to the operator and the manager to let them know if the specifications are being hit.

When there’s an exception, it alerts the operator and the farm manager. At that point, they decide whether to stop and correct an issue. It alerts what the issues are so the operator and manager can decide on the next step. With some problems, the alert goes straight to the dealer who offers support when there’s a problem. The dealer can come out to the field to make sure the downtime is limited. This is a factory out in nature.

DN: Can the automated system self-correct during its operation?

Than Hartsock: This machine in real-time is assessing the local environment to know what adjustments to make to achieve the best outcomes. The soil conditions are part of the feedback loop, and the algorithm adjusts the machine to go faster, slower, or whether to push the seed deeper. Seed-by-seed it decides how to adjust the seeding right for the optimal solution.

DN: Is consistency an important part of agriculture automation?

Than Hartsock: What the farmer cares about is that every corn plant emerges from the soil into the sunlight at the same time. You don’t want one plant to get ahead. Once planted, they all look identical so they’re all on an equal basis. When you harvest, you don’t want any pants to be behind because they will never catch up. We try to get every variable possible under control.

DN: Where does farming automation go beyond this point?

Than Hartsock: Where we’re headed is artificial intelligence used for crop production. The major step in AI will be spraying. AI can learn from the work it is doing to distinguish between a weed and a soybean plant. AI is an example of a system that gets smarter over time. The more you use it, the more it learns and adapts. The control system on the planter is not AI yet.

Rob Spiegel has covered manufacturing for 19 years, 17 of them for Design News. Other topics he has covered include automation, supply chain technology, alternative energy, and cybersecurity. For 10 years, he was the owner and publisher of the food magazine Chile Pepper.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like