'Liquid' Smart Window Helps Keep Buildings Temperate

Hydrogel allows window glass to darken and lighten depending on ambient temperature to manage energy consumption.

January 12, 2021

Scientists are looking at ways to make next-generation buildings more efficient with smart window technologies that can perform a variety of energy generating and saving functions to help regulate ambient temperature inside the buildings.

To that end, researchers at Nanyang Technological University (NTU) Singapore have developed a new liquid window panel that can perform two functions simultaneously to help reduce a building’s energy consumption and potentially contribute to the design of future smart buildings.

The technology—developed by a team at the university’s School of Materials Science & Engineering—can both block the sun to regulate solar transmission, while also trapping thermal heat that can be released through the day and night depending on the temperature inside.

Researchers developed the window by placing hydrogel-based liquid—a mixture of a micro-hydrogel, water, and a stabilizer—within glass panels. In experiments, the liquid demonstrated that it can respond to a change in temperature in the building and thus can reduce energy consumption in a variety of climates.

"Sound-blocking double glazed windows are made with two pieces of glass which are separated by an air gap,” explained Wang Shancheng, project officer at the School of Materials Science & Engineering, in a press statement. “Our window is designed similarly, but in place of air, we fill the gap with the hydrogel-based liquid, which increases the sound insulation between the glass panels."

Efficiency Challenge

While integral to building design, windows are the least energy-efficient part of it due to the ease of transmission of heat as well as cold through the glass, which has a major impact on the heating and cooling costs of a building.

To offset this, conventional energy-saving windows use expensive coatings that cut down infrared light passing into or out of a building, which helps to reduce demand for heating and cooling. However, these coatings don’t regulate visible light, a major component of sunlight that causes buildings to heat up and thus affect energy efficiency.

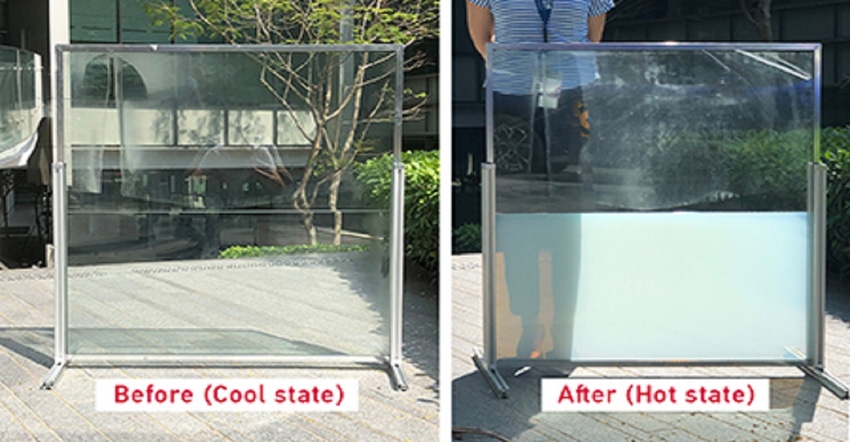

The way the smart window that the NTU Singapore team designed works is that the liquid mixture turns opaque when exposed to heat. This blocks sunlight to cool down a room and lower the ambient temperature. Once this is achieved, the window returns to its original clear state to maintain the new temperature and will change again to adjust accordingly.

Indeed, water can absorb a high amount of heat before it begins to get hot, and this capacity allows a large amount of thermal energy to be stored instead of getting transferred through the glass and into a building during the hottest part of the day. The heat can then gradually cool and be released at night, explained Professor Long Yi, a senior lecturer at the School of Materials Science & Engineering.

“By using a hydrogel-based liquid we simplify the fabrication process to pouring the mixture between two glass panels,” he explained in a press statement. “This gives the window a unique advantage of high uniformity, which means the window can be created in any shape and size."

Testing the Tech

Researchers published a paper on their work in the journal Joule. The team tested the windows in simulations using building models and weather data for four cities—Shanghai, Las Vegas, Riyadh, and Singapore. In these tests, researchers found that the liquid-based glass can reduce up to 45 percent of heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning energy consumption in buildings compared to traditional glass windows.

The glass also is 30 percent more energy-efficient than commercially available low-emissivity (energy-efficient) glass and is less expensive to produce.

The team also conducted outdoor tests in both hot (Singapore, Guangzhou) and cold (Beijing) environments. The Singapore test demonstrated that the liquid window had a lower temperature (122°F) at noon, which is the hottest part of the day, compared to a normal glass window (183°F).

Meanwhile, the Beijing tests showed that the room using the window consumed 11 percent less energy to maintain the same ambient temperature compared to a room with a normal glass window.

Based on their test results, researchers believe the window is most well-suited for use in office buildings that operate mainly during the daytime hours. The research team is now looking to collaborate with industry partners to commercialize their technology.

Elizabeth Montalbano is a freelance writer who has written about technology and culture for more than 20 years. She has lived and worked as a professional journalist in Phoenix, San Francisco, and New York City. In her free time, she enjoys surfing, traveling, music, yoga, and cooking. She currently resides in a village on the southwest coast of Portugal.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)