IoT the Extraterrestrial Holds Promise for 5G and More

Once known as the IoT of Space, the extraterrestrial placement of broadband ready communication mega-constellations is becoming a reality.

May 5, 2020

About four years ago, the IEEE Microwave Theory and Techniques Society (MTT-S) sponsored one of the first Internet of Space (IoS) discussions at the International Microwave Symposium (IMS) in San Francisco, CA.

With representation from a global community of satellite and end-user companies, the IEEE IMS Rump Session Panel explored the technical and business challenges facing the emerging IoS industry. What exactly was the IoS? Did it include both low-earth orbit and potentially sub-orbital platforms like drones and balloons? How do microwave and RF designs differ for satellite and airborne applications? These were but a few of the questions that were addressed by the panel, which consisted of professionals from Virginia Tech, ViaSat, Facebook, Boeing, OneWeb, RUAG Space and Keysight.

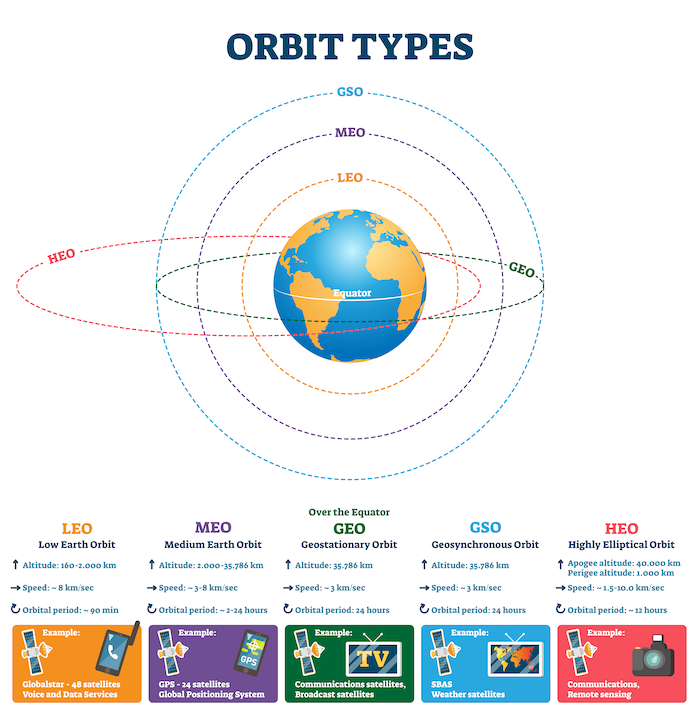

At the time of this panel, few broadband, low earth orbit (LEO) IoS communication satellites had been launched. Certainly, several existing commercial satellite Internet service providers - Viasat, Eutelsat, Hughes, Iridium, O3b Networks, and others - had been operating communication constellations across different orbits for years. But this was nothing like the mega-constellations of hundreds of individual satellites that were planned during the insuing years for the IoS broadband network systems.

Fast forward to today. Deloitte analysts recently predicted that by the end of 2020, there will be more than 700 satellites in low-earth orbit (LEO) seeking to offer global broadband internet, up from roughly 200 at the end of 2019. What does this mean to potential 5G broadband (1GHz and higher throughput) and other terrestrial Internet users?

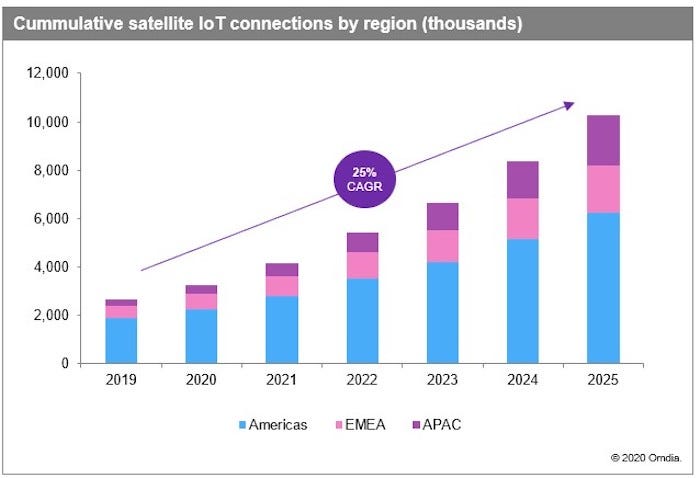

Looking ahead, Omdia analysts foresee that the installed base of satellite IoT connections will increase by nearly a factor of four in the coming years, expanding at a 25% CAGR from 2.7 million units in 2019 to reach 10.3 million units in 2025.

The Omdia report notes that, while satellite IoT will only account for a small proportion of overall IoT connections, it will support critical use cases in industries such as maritime and oil and gas. Further, the next 10-15 years will see standard terrestrial wireless IoT technologies playing a key role in enabling satellite based IoT connectivity. However, in the next five years or less, terrestrial wireless technologies will likely have only minimal impact, accounting for less than 10% of the installed base of satellite connected IoT devices in 2025.

|

Image Source: Omdia Report |

This rush into space has ignited several new ventures who hope to bring satellite-based broadband Internet access to areas underserved by existing terrestrial networks, including SpaceX’s Starlink, Amazon’s Project Kuiper, and Softbank-backed OneWeb.

But there has already been at least one casualty in this space race. At the end of March 2020, OneWeb filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection about a week after launching their latest round of satellites. According to the corporate press release, OneWeb had been engaged in advanced negotiations to secure full funding through its deployment and commercial launch. While the company was close to obtaining financing, the process did not progress because of the financial impact and market turbulence related to the spread of COVID-19.

Will this loss significantly impact the broadband space movement?

“It’s difficult to say as this process is still unfolding,” observed Sam Lucero, Senior Principal Analyst, IoT Platforms at Omdia. “OneWeb is taking several actions, including asking for current investors to provide a cash lifeline to enable the company to operate while it tries to sell its global spectrum assets, to petitioning the UK government for state financing - with the offer to move all operations from Florida to the UK. I would assume that the current 74 satellites in orbit would not be junked but could be taken over by an asset purchaser, along with the several dozen existing OneWeb ground stations, and repurposed to a new network. But that’s highly speculative.”

While the satellites and their launches probably represent one of the biggest cost factors for Internet of Space, or Internet of Extraterrestrial as they are now called, there are other consideration. For example, how will existing terrestrial wireless networks connect to these satellites?

According to the Omdia report, both established satellite companies and startups are exploring new ways to connect IoT devices. While most rely on proprietary satellite connectivity technologies to support IoT devices, several are starting to leverage terrestrial wireless IoT connectivity technologies in their network strategies - specifically the set of standards comprising LoRaWAN, NB-IoT, LTE-M, and eventually 5G NR Low Power. Connecting to these existing terrestrial protocols would help reduced costs, greater supplier diversity, and easier integration for customers.

Indeed, this was one of the issues raised by OneWeb back during the initial IEEE Internet-of-Space panel. David Bettinger, OneWeb, VP of Engineering, Communications Systems, explained that challenges were quite different on the ground side of the business equation (as opposed to the satellite side).

“One challenge is the user terminals like the devices that you put on your roof,” noted Bettinger. “They point straight up at the satellite to provide local access via an Ethernet cable, Wi-Fi or even LTE extension. These terminals are all about cost. To crack the markets we want to crack, we need to get the cost of the customer-premises equipment (CPE) – that connects to the carrier’s telecommunication channel - down yet have a device that actually points at satellites that are moving across at about 7km per second. And changing to different satellites every 3 ½ minutes.”

Today, that particular issue may not be as challenging as CPE gateways and modems are now provided by the satellite operator themselves or by a third-party vendor.

There is now doubt that the Internet of Space (or Extraterrestrials) will bring higher bandwidth and greater Internet coverage to the Earth. However, it will also contribute significantly to the amount of satellites orbiting the planet, thus increase the risk of collisions by space junk. What would happen to the mega-constellations of satellites if one or more where disabled by a collision with space junk?

“Oftentimes an operator will provide excess capacity, like more satellites in orbit than needed for normal service, in the network as insurance against the loss of any particular satellite,” explained Lucero. “Or spares could be kept on the ground, but then there’s obviously the delay to place the spare in orbit. My sense is that space junk is more of a concern at low-earth orbit (LEO) altitudes than the geostationary orbit (GEO) altitude, just given the differing levels of individual devices being placed in LEO. Space Junk is certainly an area of focus for the industry and featured as a topic at several SATELLITE 2020 panels earlier this year, for example.

Although business and technical challenges still lie ahead, in the future most customers and stakeholders will treat satellite connectivity as simply another means of getting remote data into cloud based IoT applications. For rural areas and the like where Internet connections are unreliable if even available at all, the satellite-based Internet will act as an IoT market driver. For all other users, especially in 5 to 15 years as 5G communication becomes readily available, the IoT of Extraterrestrials will bring amazing broadband speeds to everyone.

|

Image Source: Adobe Stock |

RELATED ARTICLES:

John Blyler is a Design News senior editor, covering the electronics and advanced manufacturing spaces. With a BS in Engineering Physics and an MS in Electrical Engineering, he has years of hardware-software-network systems experience as an editor and engineer within the advanced manufacturing, IoT and semiconductor industries. John has co-authored books related to system engineering and electronics for IEEE, Wiley, and Elsevier.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like