Botched Construction Job Leads to Finger Pointing

August 21, 2012

A client is irate. They are saying the retrofit fire protection system I designed (and that their contractors are installing) is malfunctioning. They have had two unintentional discharges of halon gas, a fire suppression element, and they are blaming my employer for the malfunctioning equipment, and more specifically, me for an improperly designed system. My employer, in a veiled threat, said I had better figure out what was going on. Cue that sinking feeling you get when you realize you may have really done something wrong.

The job was an electrical retrofit and extension. They replaced everything that had electricity flowing through it, and they were extending the existing piping system to protect a larger area. The new control panel and supporting electrical devices were installed, powered up, and tested. Everything checked out.

These guys then continued to install the mechanical upgrade, while the system was active and armed. I was assured that the fire protection system had been locked out. Typically, locking out a system means that the tanks containing the agent cannot possibly discharge because they have been electrically and/or mechanically disconnected from the system. I soon learned that the contractors, professionals, had done neither of these. Instead, they tried to hotwire the control panel. Their crew had wired an alarm bell panel output into the abort input.

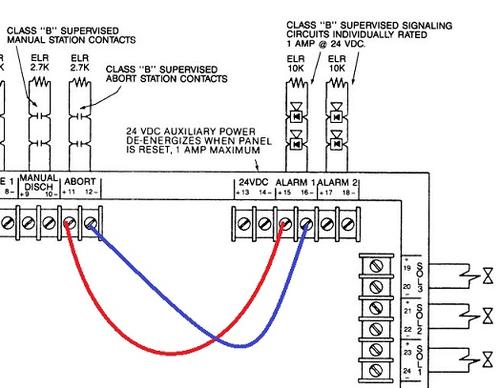

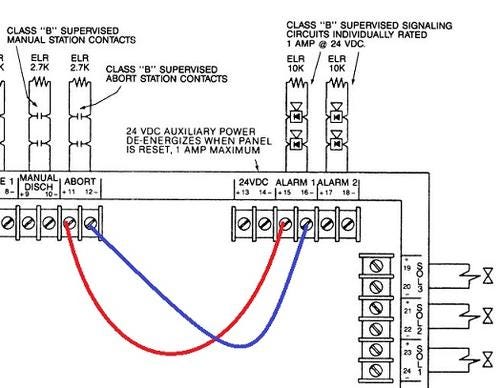

They thought that the 24V DC, which goes active for a preprogrammed discharge, would power the abort input and fool the panel into thinking someone was holding down the abort button, thereby preventing discharge. (A note about clean agent systems: They all have abort switches to delay the agent discharge. This is for someone who thinks the alarm may be in error, or is trying to hold off the agent release for people who have yet to exit the protected area.)

I found out what they had done the next day, but not before the system discharged a third time. Here is what they did not know -- the abort input is not looking for 24 volts. It is expecting a button mounted on a wall near an exit somewhere to electrically short the abort input terminals.

Fire control panels have supervised inputs. This works by applying a voltage to the input circuit. Each input circuit has an ELR or "end of line resister" as the last element in a parallel array of input devices. This supervisory voltage sets up a current that is monitored by the control panel. A switch closure results in increased current flow. No current flow indicates a severed circuit and will trigger a trouble condition at the panel.

Also, a broken wire on a parallel element wired after the ELR will not be detected by the panel. This is a common error during installations. For instance, ELRs are installed right at the panel terminal blocks for an initial panel check and then they will forget to put them at the end of a circuit during the rest of the installation, resulting in a circuit that is not being monitored for integrity.

The accusatory statements and threats of litigation against me stopped immediately following my explanation that their hotwiring did nothing. It was their fault for working a construction job while the alarm panel was active. It is hard to believe that so-called experts come in to do a job, and they pretend to know what they are doing. As my years in the fire protection industry continued, I encountered incompetence more times than not. When lives are at stake, shouldn't people's bonafides be tested?

Tell us your experience in solving a knotty engineering problem. Send stories to Rob Spiegel for Sherlock Ohms.

Related posts:

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like