Would You Let Your Kids Play With Atomic Energy?

November 10, 2014

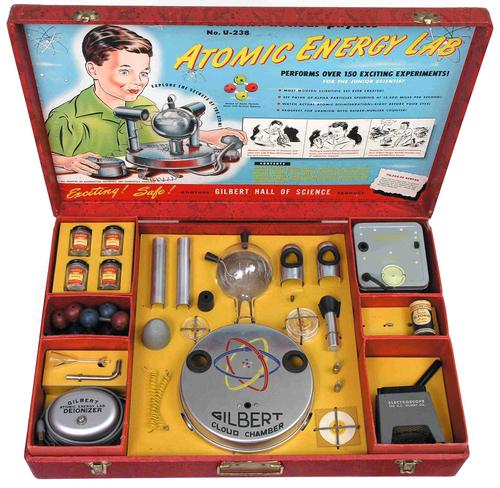

Many of us grew up with electronics kits, Lego bricks, and Erector sets. A very small number of kids in the early 1950s, however, got to play with real atomic energy. The Gilbert U-238 Atomic Energy Lab was only manufactured for two years, and sold for $50 (today's equivalent of $493.84, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics' Inflation Calculator). It offered young people the opportunity to watch radioactive decay with a spinthariscope, measure the radioactivity of uranium ore with an electroscope, watch the tracks formed by alpha particles in a cloud chamber, and even prospect for uranium using a Geiger counter.

The set came with an educational comic book titled Dagwood Splits the Atom, in which comic strip characters including Dagwood, Blondie, Popeye, and Mandrake the Magician explained the basics of nuclear physics. It also came with a copy of an official US Geological Survey-Atomic Energy Commission publication entitled, Prospecting for Uranium. The kit's packaging advertised a $10,000 bounty offered by the US government for locating uranium deposits -- suggesting, perhaps, that the kit could more than pay for itself (if only you were lucky enough to find some uranium).

Included in the set were samples of four uranium-bearing ores: carnotite, torbernite, uranite, and autunite. The first three radioactive ore samples were provided in sealed glass containers. The autunite came in a screw-top jar; the set's instruction manual encouraged readers to take it out of the jar and handle it. The set also contained three radionuclide samples: an alpha-particle source (lead-210), a beta-particle source (ruthenium-106), and a gamma-particle source (zinc-65). The cloud chamber came with its own, more-powerful, alpha-particle source (polonium-210). The Gilbert company offered to replace any of the radioisotopes if they lost their radioactivity.

How dangerous was this toy? It's unlikely that handling any of the ores or radioisotopes for a brief period would pose a significant risk. However, ingesting or inhaling any of these substances would be another story. The polonium-210 used in the cloud chamber is particularly hazardous. In 2006, a few micrograms of polonium-210 were allegedly used in the assassination of former Russian spy Alexander Litvinenko.

A toy like this would definitely be frowned upon today. In 2012, Bridgestone recalled nearly 10,000 bicycles in Japan because the stainless steel used to manufacture the baskets had been contaminated with small amounts of cobalt-60. Similarly, in 2013, Petco recalled stainless-steel pet food bowls that contained cobalt-60. The source of the radioactive material was speculated to be scrap medical equipment that had been melted down. In either case, the potential exposure for anyone (human or animal) using the products would have been much less than with the Gilbert U-238 Atomic Energy Lab.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like