How to Build Your Own Robotic Tail

Robotic tails have longed been used as costume enhancements for cosplayers but now they may have a role for space travelers.

June 25, 2020

Humans seem to be always on the lookout for augmentations using electronic and mechanical technologies to physically enhance their bodies. This is done by attaching or implanting some type of device to improve their capability to go beyond current human experience, e.g., 3D-printing an appendage such as a third thumb or – more recently – a tail.

|

Third Thumb Project. (Image Source: Dani Clode) |

Many of today’s augmentations offer fairly simple improvements. Consider the example of an extra thumb. Dani Clode, a grad student at London’s Royal College of Art (RCA), has created an extra digit with her third thumb project. This augmentation is a 3D-printed prosthetic that simply extends a user’s grip. The extra thumb straps onto the hand, which connects to a bracelet containing wires and servos. The wearer controls the thumb via pressure sensors located under the soles of their feet. Pressing down with one foot will sent a signal via Bluetooth that will cause the thumb to grasp an object.

Some of these simpler human augmentations are even being considered as improvements for astronauts. Similar to a third thumb, a monkey or cat tail could provide extra dexterity and balance (in terms of controlling momentum) in weightless conditions.

MIT Labs has recently engaged in developing a seahorse-like augmented prosthetic for use in weightless or microgravity environments. Officially, the SpaceHuman is a soft robotic prosthetic for space exploration. It was designed to move around the body, “to grasp objects and handles in microgravity, protecting the wearer from injuries that might occur while floating in a confined habitat, while providing an adaptable and kinematically stable base.”

The SpaceHuman prosthetic tail has undergone numerous computational simulations to model its behavior in microgravity and has even been worn and tested on a Zero-G flight. The additive or 3D-printed tail was developed using several ribbed tubes made of silicone. Those tubes are comprised of 36 air chambers that can be inflated into different configurations via 12 battery-operated air pumps attached to a waistband, thus giving the tail the ability to curve or lengthen.

|

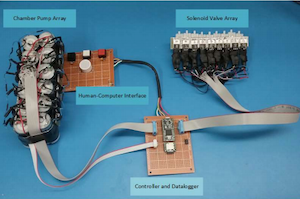

Electronics and controls for SuperHuman Tail. (Image Source: MIT Media Lab Tail Electronics) |

Sensors in the tail will eventually respond to the users movements, e.g., grabbing onto nearby surfaces to aid stability in microgravity environments. Other scenarios for the tail might include it acting as a rudder while moving from one point to another in space or even picking up objects. An object-tracking camera in the user’s backpack will feed information into the prosthetic to identify colors and materials.

In addition to MIT Lab, Keio University in Japan has also recently designed a wearable robotic tail. Their enhancement is not for microgravity environments but to help elderly here on Earth keep their balance.

While both of these augmented tails use 3D-Printing materials, actuators and electronics that are readily available, neither university offers their design details to the general public. For now, hobbyist and DIY enthusiasts will have to set for more basic tail designs:

Maker Thingsverse offers several designs for robotic tails:

Animatronic Tail by Pedrodeoro - This is a prototype animatronic tail, OpenScan designed 3D printed on a 3D printer and controlled by Arduino.

Ekobots - Snake Charger Tesla by jsirgado - Make and control your own Tesla Snake Charger. Print how many "body" pieces you want to make a big snake.

Hackaday:

|

Ekobots Snake Charger for Tesla. (Image Source: Snake Charger by jsirgado, CC) |

RELATED ARTICLES:

John Blyler is a Design News senior editor, covering the electronics and advanced manufacturing spaces. With a BS in Engineering Physics and an MS in Electrical Engineering, he has years of hardware-software-network systems experience as an editor and engineer within the advanced manufacturing, IoT and semiconductor industries. John has co-authored books related to system engineering and electronics for IEEE, Wiley, and Elsevier.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like