Open Source IP is Best Not Forgotten

Software and hardware intellectual property must be management – even by engineers – to avoid legal entanglements and broken designs.

June 2, 2020

Without the creation, discovery, licensing and sharing of intellectual property (IP), the modern world of electronics would look very different. In the semiconductor chip space, IP has enabled the creation of highly complex system on chips (SoCs) and acompanying software systems, which are the cornerstones of today’s consumer electronic markets such a smartphone and other mobile devices.

Given the importance of IP to electronic and mechatronic design and manufacturing, you’d think it would be a highly prized and well-managed asset. Such is not the case, according to a recent 2020 Open Source Security and Risk Analysis (OSSRA) report. One of the key findings of the report, which was produced by the Synopsys Cybersecurity Research Center (CyRC) and focused solely on open source software components, was that 91% of commercial applications contain outdated or abandoned open-source components —a potentially serious security threat and legal concern.

Further, the report revealed that 99% of the 1,250 commercial codebases audited contained open-source code, with open source comprising 70% of the code overall. According to a press release, what was, “more notable is the continued widespread use of aging or abandoned open source components, with 91% of the codebases containing components that either were more than four years out of date or had seen no development activity in the last two years.

The four main findings were:

Open-source adoption continues to soar. (36%).

Outdated and “abandoned” open-source components are pervasive.

The use of vulnerable open-source components is trending upward again.

Open-source license conflicts continue to put intellectual property at risk.

Open source software is no different from any other software in that its use is governed by a license that describes the rights conveyed to users and the obligations those users must meet.

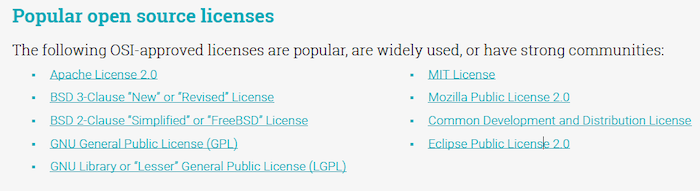

The Open Source Initiative (OSI), a nonprofit corporation that promotes the use of open source software in the commercial world, defines open source with 10 criteria and lists 82 OSI-approved licenses, with nine being “popular, widely used, or having strong communities.”

|

(Image Source: Open Source License, Synopsys 2020 Open Source Security and Risk Analysis (OSSRA) report) |

Analyses from the OSSRA report indicates that the 20 most popular licenses cover approximately 98% of the open source in use. One application that uses a lot of open source licenses is blockchain project. The report notes that one such project used a GNU Affero General Public License (AGPLv3) that generally states, “if you use a licensed component (or a derivative) in your software, you must make your source code available under the same conditions as the original component.” Many companies are reluctant to open their own source code to general use and are wary of any ensuring compliance issues.

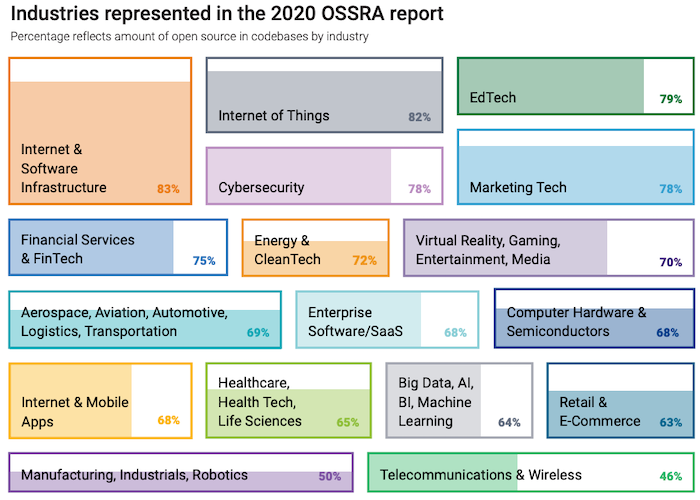

|

Image Source: Synopsys 2020 Open Source Security and Risk Analysis (OSSRA) report. |

Engineers reading the OSSRA report might be tempted to say, “OK, so what? Do I really need to worry about open source software (or hardware) compliance and IP management issues in addition to all the critical design, verification or manufacturing work that I have to do?”

The question is particularly troublesome for chip hardware engineers. Warren Savage, Visiting Researcher at the University of Maryland and former CEO of IPextreme, acknowledges the problem: “Open source hardware (i.e. IP) has been something that has intrigued the semiconductor community for a long time. However, unlike its cousin, open source software, it has failed to materially impact the semiconductor IP market. There are technical and legal issues at play. Given the multi-million-dollar cost of wafers, few engineering managers are willing to bet their job if the IP would turn out to have latent bugs and or worse—patent infringement issues.”

Michael Munsey, while working at Dassault Systems, once answered the question this way: “Most designers and verification engineers understand the need for IP reuse in system-on-chip (SoC) design. But few seem aware of the management and governance that such IP will require. For example, as companies reuse more internal IP and acquire more external IP, they’ll need to create a cataloging system. This catalog will lead to a grading of IP based upon its usage and known defects. Just as with internal IP, the third-party IP must be tracked not only for bug issues but also for royalty and licensing payments. For large companies, all of these management activities will need to happen across a multiple of projects.”

The last point has become more critical for consumer electronics and other mass markets. Handling multiple projects often within a product family – like a smart phone – requires the management of slightly variant designs. Olivier De Percin, VP, Digital and Industry, at Dassault Systemes, noted that mass customizations in the design will also mean having many variants in the field. Keeping track of both the design, manufactured and field variations requires the capability to manage all resources but especially all of the IP.

Another reason to maintain a database of all hardware and software IP used in a design is to safeguard against infringements. The big problem facing most companies is that they don’t know what IP they have. One reason for this is the poor internal governance within corporate databases. Often, companies simply lose track of where the IP is used. There should be a managed pedigree or record of IP heritage.

Like it or not, the governance and management of IP is the primary way to deal with outdated and abandoned bits of design and even manufacturing code. The question is, who’s going to do it?

|

Failure to comply with open source IP has legal ramifications. (Image Source: IP Management Compliance, Adobe) |

John Blyler is a Design News senior editor, covering the electronics and advanced manufacturing spaces. With a BS in Engineering Physics and an MS in Electrical Engineering, he has years of hardware-software-network systems experience as an editor and engineer within the advanced manufacturing, IoT and semiconductor industries. John has co-authored books related to system engineering and electronics for IEEE, Wiley, and Elsevier.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)