3 Reasons Why Engineers Should Embrace Digital Product Passports

Digital product passports provide engineers access to range of product data that could ease design and engineering decisions.

A digital product passport (DPP) is a relatively new phenomenon, but one that has big potential benefits for engineers. A DPP collects and shares product data from the product’s entire lifecycle. This can include manufacturing details, certifications, and usage history. By showing how the product was manufactured, what’s inside it, and where it’s been, digital passports can be used to illustrate a product's sustainability and recyclability potential.

For instance, if my smartphone had a DPP, it might list the types of metals, plastics, and other materials present in the device, along with their respective percentages. It could also list any harmful or environmental unsound materials like lead, mercury, cadmium, or brominated flame retardants present in the phone.

A DPP might also include information about the device's power consumption, battery life, and energy-saving features. It could even mention compliance with ISO 14001, which is a list of standards for any environmental management system, or EPEAT (Electronic Product Environmental Assessment Tool).

But how would DPPs be relevant to your work as a product engineer? In short, a DPP enables better modeling, so it’s going to make your life a lot easier.

Digital Product Passports Provide a Single Source of Information

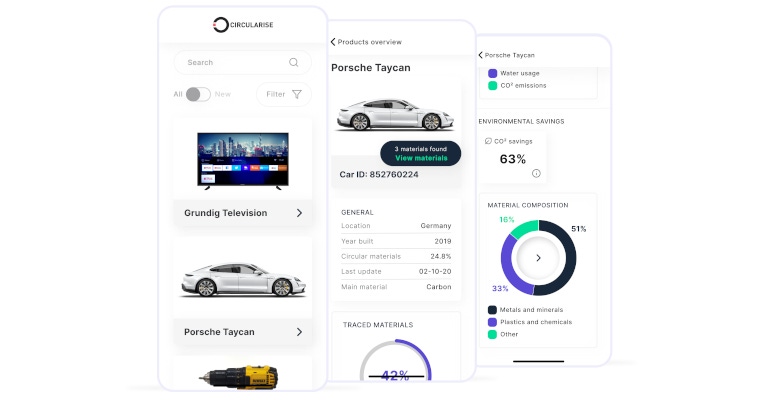

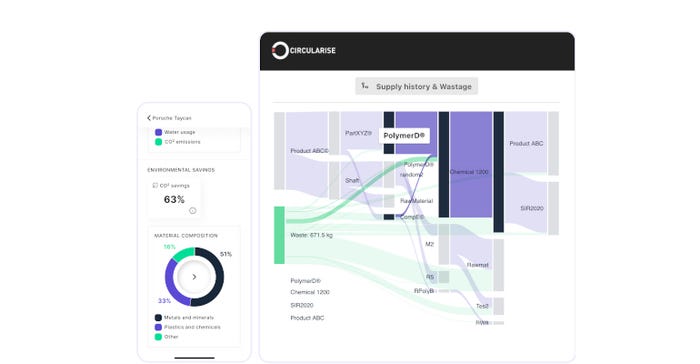

First, a DPP offers a repository of centralized information about a product’s critical specs. Anyone can access technical specifications, design documents, architecture diagrams, component details, and any other relevant data in one place, making it easier to understand the product's design and functionality.

Right now, most engineers I know spend a large proportion of their time chasing down specs and trying to find manuals on multiple platforms, including emails, Slack threads, physical manuals, and more. By putting all the information in one easy-to-access place, usually in the form of a QR code attached to a product, a DPP cuts down significantly on the detail-gathering stage of product design.

But this data isn’t just useful to engineers. Engineers work with designers, quality controllers, and additional stakeholders at a manufacturing company. Using a DPP makes it easier to collaborate and communicate with those people. That central repository of data also offers a place where collaborators can access and update the passport, ensuring everyone is on the same page and reducing misunderstandings.

A DPP ensures there’s a definitive source of info regarding a product’s design history and lifecycle. The passport could maintain a history of design changes, updates, and versioning. This also allows engineers and other stakeholders to track how the product has evolved over time, which makes it easier to identify potential problems and make improvements.

Accurate Product Modeling

DPPs also play a role in enabling more specific and accurate product modeling. Many engineers are familiar with creating 3D models to design and engineer certain products. But those are usually based on secondary generic data. For example, when starting the design process for a new smartphone, engineers would begin with generic data sourced from publicly available sources or industry manuals. This data could include general specifications for components like the processor, camera, display, and battery.

In contrast, a DPP would allow designers and engineers to make decisions based on real primary data from the supply chain. In contrast to my example above, a DPP would provide primary data sourced directly from the specific suppliers and manufacturers of each smartphone component. Engineers would have access to detailed datasheets and technical specifications for the actual processor, camera sensor, display panel, and other critical components that will be used in the device. This data is much more precise and accurate than generic information available elsewhere.

Evolving Requirements

The engineer’s job is slowly changing. In the past, engineers designed a product, tested it, sent it out into the world, and then the process was over. Today, as interest in sustainable engineering surges, companies need engineers to design circular products, ones that can be readily reused or recycled, allowing as little as possible to go to waste.

Moreover, with DPPs, products that have recyclable components can be clearly documented as such, and all information on circularity can be readily available for any relevant party. A DPP is thereby a critical platform for engineers to document information so that any manufacturer, supplier, or customer who comes across the product will know how to make the most use of its parts.

It’s also worth thinking about the trend toward product longevity. When tasked with designing products with long lifecycles, engineers can use a digital product passport to support and maintain legacy systems. They can understand the product’s history, its repairs, and even past software updates to better maintain it. These can be used for ongoing maintenance even years after the product's initial release.

Contemporary product design involves creating products that are built to last and withstand prolonged use. Designing for durability focuses on using high-quality materials, robust construction, and thoughtful engineering to ensure that products have a longer lifespan. This approach reduces the need for frequent replacements and contributes to a more sustainable and circular economy.

Another key aspect of contemporary product design is the emphasis on making products repairable and suitable for reuse. Designing products with repair in mind involves using modular components, easily accessible parts, and intuitive disassembly methods. This design approach facilitates the repair process, extending the product's life and reducing overall waste. Additionally, designing for reuse encourages the repurposing and refurbishment of products, contributing to circular practices by keeping products in use for as long as possible.

Finally, although DPPs might mostly be an opt-in convenience for now, I expect other countries and regulatory bodies will soon follow in the EU’s footsteps and make DPPs mandatory. If you’re wondering how you can best prepare, I highly recommend you read the World Business Council for Sustainable Development’s guide on the subject.

The Digital Product Passport Is a Critical Tool

The idea of a digital product passport may seem unwieldy now. I don’t know many engineers who have enough free time at the moment to be excited about the prospect of developing a brand-new workflow.

But, regardless of the sentiment, DPPs seem an inevitability. Consumers and governments have an undoubted interest in sustainability and circularity, which will soon be backed by regulatory enforcement. So, if DPPs haven’t yet arrived at your workplace, I expect they will soon. In my opinion, the best thing engineers can do now is have an open mind toward the benefits, embrace the idea, and get excited about contributing to a more-sustainable future.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like