An Electric Car Too Soon

June 10, 2016

Back in 1995 I built an electric car based on a 1974 Honda Civic (Figure 1). It showed me some of the serious limitations of electric propulsion, as well as my own limitations as a one-man design team. It used an 8-inch Advanced D.C. motor and a 144V, 500A Curtis controller. The GVW (gross vehicle weight) of a 1974 Honda Civic is 2,400 lb. The finished car weighed 2,200 lb. This would allow one driver, no passenger, and a little luggage. The car would not be able to drive to Santa Cruz and back to Silicon Valley, as there is an 1,800-foot hill in between. I could be gentle with throttle and get 30 miles of range. If I stomped the pedal at every light the batteries were dead after 11 miles.

My own limitations were just as severe. While I had a college class on motors, I really did not understand the implications of using a DC motor versus an induction motor versus a BLDC (brushless DC) motor in a car. DC motors have maximum torque at stall, and are great for drag race applications. The motor and controller I used were intended for fork trucks and golf carts. This is why my DC Honda would scoot along the freeway at 80 mph, but it sure could not do that for very long. I was equally naive about my battery choice. Back then, you could use golf-cart lead-acid batteries for longevity or pick RV/marine batteries for cost and weight. I replaced the original golf-cart batteries (Figure 2) and went the cheap route with RV/marine batteries.

In retrospect, I jumped the technology curve. Large lithium-ion batteries were not around. The other realistic alternative would be aircraft nickel-cadmium batteries. They priced out around $20,000 for the same capacity as my 10 66-lb SCS-225 Trojan batteries. Those set me back $974.90 in 1995; today they would cost $1,600.

Now I am not saying I completely botched the job; I am a GMI- (General Motors Institute) trained engineer. I worked for GMC Truck and Ford Motor in Detroit. That is why the weight of the car and driver did not exceed the GVW of the car. I picked a small light car to start. I took out the aircraft generator the previous owner tried to use and bought that shiny new Advanced D.C. unit. I knew that weight distribution was important. By putting the batteries in the passenger compartment, it both shared the weight between axles and reduced the polar moment of inertia of the vehicle. Indeed, Figure 2 was a previous owner's attempt. The car was still too heavy in the rear, so I took out the passenger seat and put four batteries on the floor-pan up front. I installed an E-Meter to monitor my voltage and current in real time. The thing I am proudest of is that I actually finished the project and got the car registered to drive.

The devil is, indeed, in the details (Figure 3). I soon learned that despite having 10 batteries, I still needed the regular car battery to run the lights and wipers and radio. So now I needed to buy another power supply to draw from the 120V stack and charge the 12V car battery. The car was heavy, right at GVW, so I wanted to keep the car's original vacuum assist power brakes. So that meant the addition of a vacuum pump, a reservoir, and a controller. All those batteries needed big thick cables, so that also meant sourcing them and the terminals and a big crimper you set with a hammer. The controller needed a big heat sink and a fan -- another $148. I modified the machined aluminum adapter plate to mount the motor to the transmission. That cost $290. A throttle potentiometer was $65. A Heinemann dc circuit breaker was $175. The cable lugs and crimper were $50.

READ ABOUT MORE DIY PROJECTS ON DESIGN NEWS:

And time, lots of time, to assemble all this stuff and get it working. I ended up scrapping the car in 2001. The batteries were ruined but I still have the motor and controller. I hope to use it to make a Harley generator test stand. When I wrote an article in 2007 that maintained that electric cars did not yet make sense, people thought I was an anti-EV Luddite. That is not at all true, I just thought the technology was not yet ready. Now that thousands of engineers have spent billions of dollars, the proof is in the pudding.

Electric cars are viable. I have a bad case of range anxiety, so I would buy a Volt. A few experiences limping down Lawrence Expressway in Santa Clara, Calif. at 10 mph, before the batteries die completely will give anyone a bad case of range anxiety. But engineers can take pride that it only took nine years to develop electric cars that are practical, at least for short distances.

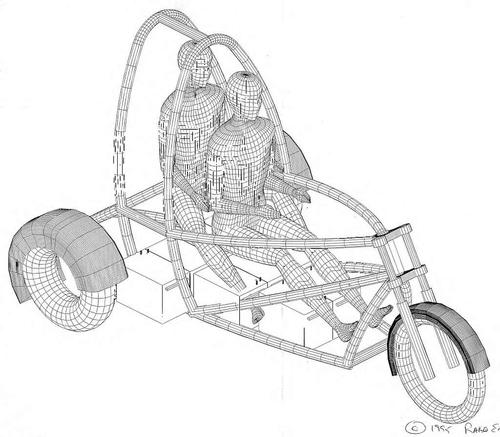

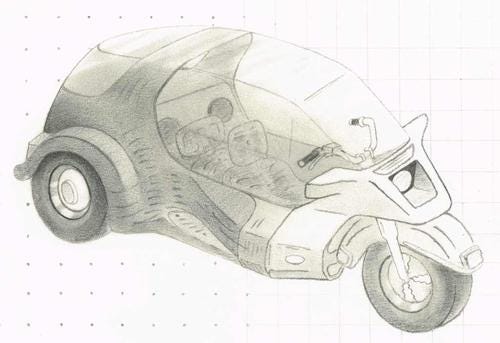

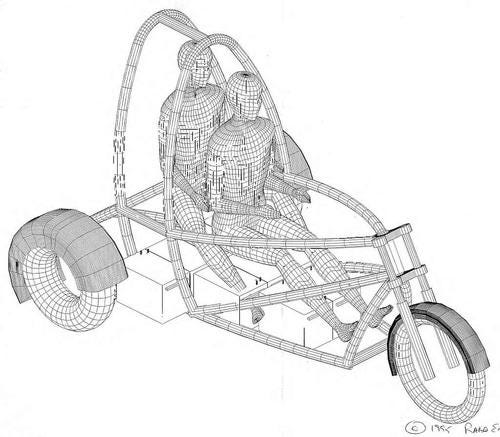

My dad had a saying about projects: "They start out like a castle and end up like an outhouse." This Honda EV was just the test buck for a 3-wheeled EV that I wanted to design from scratch (Figure 4). I do think the power-train might have worked better in a trike, and it would be legal to use in the commuter lane. The curb weight of a 1974 Honda Civic is only 1,356 lb. Hope would be you could halve that with a custom trike. Using lithium polymer batteries and a smaller motor, it might be possible to get 40 miles of range, but it is still doubtful it could go over the Santa Cruz mountains and get back home. It would be cheaper and easier to just go buy a Nissan Leaf. And then you get a real car with real safety features.

I learned one big lesson. Don't spend time and money designing things that you can just go out and buy. Experience is a cruel teacher. It gives you the test before the lesson. I do have to admit the project taught me a lot, and it was fun. That is a perfectly valid reason to do it. Just don't think you are going to start a new car company in your garage. I would not even attempt that trike design with $15 million in the bank.

As an auto engineer, I can tell you, the cost is not in the CAD work or even the prototype assembly. The cost is in testing. These days there are too many CAD designs being touted as working hardware. When I was at Ford Motor we had test jigs to run windshield wiper motors. There was "calibrated dust," an ANSI or SAE standard grit that got put on the joints. We knew that dry windshields don't use as much torque as damp-dry glass. The sprinklers were set up for that. All this is just for one small ancillary system. Designing a whole vehicle takes a whole lot of money, and a whole lot of blood, sweat, and tears from a whole lot of engineers.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like