What is a Dual-Clutch Transmission?

No, a dual-clutch transmission doesn't require two clutch pedals. But how does it work?

New cars are commonly built with dual-clutch transmissions (DCT), but the idea of such a thing can seem puzzling. Why would a transmission need two clutches, anyway? And where’s the clutch pedal? Why do new sports cars like the Chevrolet Corvette, Ford Shelby Mustang GT500, and Ferrari SF90 Stradale use them instead of the familiar H-pattern manual-shift transmissions?

The DCT is an automated transmission, so it shifts gears by itself, or in response to clicks from steering wheel shift paddles, like a traditional automatic transmission. But rather than a conventional automatic’s hydraulic torque converter spinning planetary gearsets, the DCT uses a conventional friction clutch spinning regular manual transmission gearsets.

A DCT doesn’t have a clutch pedal, because the clutches are computer-controlled. It needs two clutches because it is actually two separate transmissions, mounted in a straight line.

What Is a Dual Clutch Transmission?

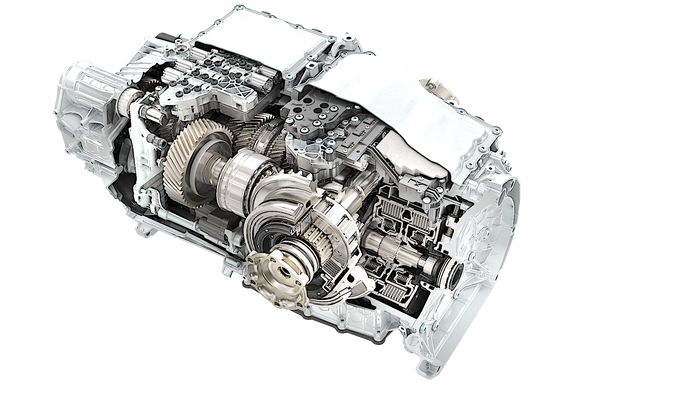

“A dual-clutch transmission is effectively two manual gearboxes that have clutches actuated by computers on a concentric shaft,” explained Ed Piatek, Corvette chief engineer. The clutches are also mounted inline, behind the engine’s flywheel, and connected to the transmission’s input shaft. Or, more accurately, the transmissions’ input shafts.

“You’ve got a shaft that has your even-numbered gears, 2, 4, 6, and 8, and [another one for] your odd gears, 1, 3, 5, 7, and you can be simultaneously disengaging one shaft while you are engaging another one,” he continued. “So it is quicker than a human being could shift a manual transmission.”

One clutch connects to a hollow outer shaft that spins the gears in the even-numbered gears, while the other one bolts to a slender inner input shaft that spins inside the other one and sends power to the “second” transmission with the odd-numbered gears.

The computer-actuated selectors shift between gear sets, while the clutches switch between the two internal transmissions. Open one clutch and simultaneously close the other and the transmission shifts from first gear to second. After that, the transmission control computer monitors the driving conditions and pre-selects the gear likely to be used next. When the time comes, the two clutches switch states again.

What Is it Like?

This lets gearchanges happen almost instantaneously and almost imperceptibly. This rapid change minimizes any time coasting, so DCT-equipped cars are faster than those with other kinds of transmissions, which is especially important for high-performance models. This is why new cars like the 2020 Chevrolet Corvette and the 2020 Ford Mustang Shelby GT500 both employ DCTs.

“A traditional car, while you are shifting, the car is actually decelerating because the engine is not connected to the wheels,” observed Corvette executive chief engineer Tadge Juechter.

Because it is built on manual-style transmission with friction clutches instead of a planetary automatic with a hydraulic torque converter, the DCT is a more efficient way to deliver automatic gearchanges.

The challenge for manufacturers is calibrating the clutch action to be smooth and developing durable clutches. Many use motorcycle-style wet clutches to control clutch temperatures with an oil bath. Very low speed movement is the strength of torque converter systems, so that is a tough aspect of calibrating DCTs, along with the challenge of programming the predictive gear shift algorithm.

The result is a car with better performance than any other type of transmission, with better efficiency than that of even a manual transmission, so we will be seeing more of these throughout the remaining lifespan of combustion engine-powered cars.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like