Whatever Happened to NASA's X-30?

August 8, 2016

NASA's recent announcement of its all-electric experimental aircraft, called the X-57, was big news, resurrecting the pioneering spirit of the agency's early days. Still, in terms of raw ambition, it paled in comparison to the Holy Grail project of a quarter-century ago, the X-30.

The X-30, better known as the National Aerospace Plane, was the ultimate example of NASA daring -- a project so big and so far-reaching that even some of the brightest and most optimistic engineers were intimidated by it. In another sense, though, it illustrated a mindset of a bygone era -- in the world of NASA, no concept was too grand to be considered.

"It was certainly one of the most challenging projects in American history, given the amount of stretch needed to get where they wanted to go," Bill Barry, chief NASA historian, told Design News recently.

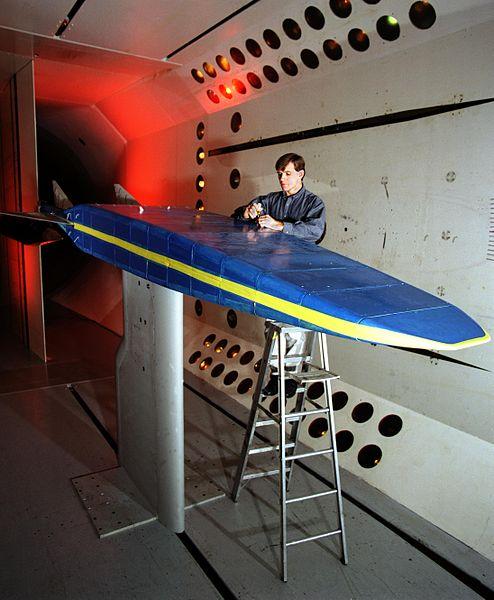

Click on the image below to start the slideshow

The National Aerospace Plane captured the imagination of the country. It was a publicist's dream -- a single-stage-to-orbit aircraft that could be piloted into earth orbit like a hypersonic Cessna. In 1986, President Ronald Reagan called it the "Orient Express," an aircraft that would take passengers from New York to Tokyo in two hours, raising the hopes of aerospace buffs around the world.

Long and sleek, the X-30 would reach speeds of Mach 25, or about 18,000 miles per hour. Instead of taking off from Cape Canaveral amid thunderous belches of smoke and flame, it would roll down a conventional runway. And instead of dropping rocket stages one-by-one into the ocean, it would roar toward the heavens, propelled by a combination of jet engines and permanent rockets. By the late 1990s, NASA engineers hoped to watch it take off from Edwards Air Force Base in the Southern California desert, and fly to the Midwest and back again, in less than half an hour.

The Astronaut as Engineer. Come hear George Leopold talk about NASA's beginnings and one engineer's pivotal role in winning the Space Race in his keynote at the Embedded Systems Conference, Sept. 21-22, 2016 in Minneapolis. Register here for the event, hosted by Design News’ parent company, UBM.

The Astronaut as Engineer. Come hear George Leopold talk about NASA's beginnings and one engineer's pivotal role in winning the Space Race in his keynote at the Embedded Systems Conference, Sept. 21-22, 2016 in Minneapolis. Register here for the event, hosted by Design News’ parent company, UBM.

To make it happen, NASA engineers targeted a laundry list of emerging technologies for further development. They needed a propulsion system that would take them beyond the realm of air-breathing jet engines. To handle temperatures of 3,000 degrees on the aircraft's skin, they planned to employ a combination of titanium metal matrix composites, carbon-carbon composites, and graphite epoxies. For cooling, they hoped to use the aircraft's fuel: "slush hydrogen," chilled to -435F.

"When it flies, it will be like a fireball travelling through the sky," one high-ranking X-30 engineer told Design News in 1992. "It will look almost like the sun travelling overhead."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)