Boeing: New Enclosure 'Keeps Us From Ever Having a Fire'

March 15, 2013

The Boeing Co. took the issue of 787 battery fires head-on last night, definitively declaring that with pending modifications to its lithium-ion battery packs, a "fire can't begin, develop, or be sustained."

Speaking at a technical briefing in Tokyo that was broadcast live on the Web, Boeing executives defended the performance of the embattled 787 batteries in recent overheating incidents, and added that its engineers have strengthened the design of the packs with a number of technical enhancements. Most important, they said, is the addition of a new enclosure that prevents fires.

"I want to be very, very clear on this point," said Mike Sinnett, vice president and chief engineer of the 787 program. "This enclosure keeps us from ever having a fire to begin with. That's the number one job of this enclosure. It eliminates the possibility of fire."

In a teleconference that lasted approximately an hour, Sinnett laid out a number of fixes for the battery packs, but most strongly emphasized the capabilities of the enclosure. The enclosure, he said repeatedly, would eliminate the possibility of fire and vent gases through a dedicated line. It would also protect the electronics bay and any surrounding equipment from heat vented by the battery during an incident.

"If a [battery] cell were to vent, it would vent into this enclosure," he explained. "It ruptures a 'burst disc' in the enclosure, which allows all those gases to go immediately overboard."

The key to preventing fires is to carefully control the amount of available oxygen, Sinnett said. Describing a potential scenario, he explained that the pressure disc in the rear of the enclosure would open after about 1.5 seconds of cell venting. Vented electrolyte would then entrain the air inside the enclosure and "take it overboard... So as long as we keep the vented air out of the battery enclosure, there's no oxygen to support combustion."

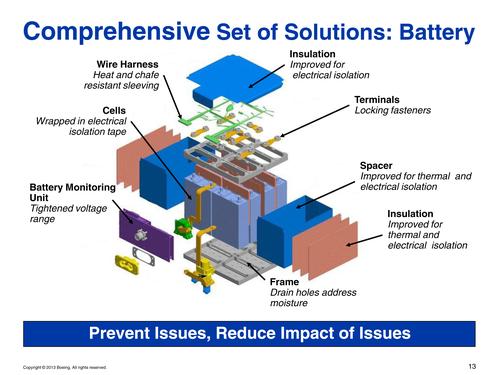

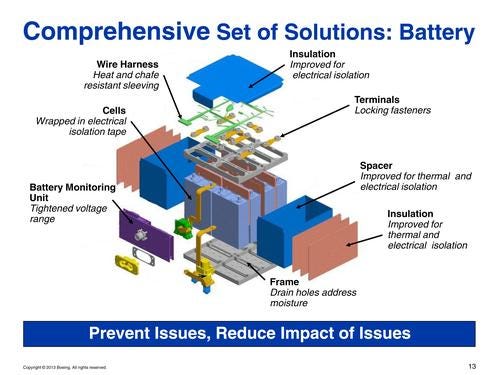

Sinnett also detailed a number of other fixes for the lithium-ion battery packs. He said engineers wrapped the cells in an electric isolator to make sure they can't short circuit, tightened nuts on top of the plate that connects the cells, added drain holes to make sure there was a path for moisture to exit, improved the heat resistance of the wire bundles on top of the battery, added heat-resistant sleeves to prevent wire chafing, and employed dielectric isolators above, below, and around the battery. All of those changes are aimed at reducing the possibility of ignition, he said.

To reduce the possibility of overcharging, Boeing engineers also dropped the upper voltage limit of the battery and raised the lower limit. Dropping the upper limit reduces the potential energy in the battery, while boosting the lower limit protects against a deep discharge event that can cause damage to a cell.

Sinnett defended the performance of the lithium-ion battery packs to date, contending that there was no fire in the Takamatsu incident. He also said that other battery chemistries have been known to have problems.

"We use lead-acid in some of our airplanes. We use 'ni-cad' in some of our airplanes. And it's surprising for many people to know that in the last 10 years, there have been thousands upon thousands of battery failures on commercial airplanes. Many of those have resulted in smoke and fire events."

Boeing has been testing its new battery design for about six weeks and is about one-third of the way through its certification plan. During tests, engineers have been able to demonstrate that when the battery vented, the enclosure contained no vented electrolytes. Using test rigs over approximately 60,000 hours, they've also been able to show that no fire is possible inside the battery, according to Sinnett.

Battery experts contacted by Design News questioned the solution, however, especially with regard to no oxygen being available for combustion. "There's oxygen in the positive electrode," Donald Sadoway, John F. Elliott Professor of materials chemistry at MIT, wrote in an email to Design News. "If the temperature exceeds a certain value, oxygen is liberated and fans the fire."

"Inside the battery, there are all the necessary ingredients for thermal runaway," added Elton Cairns, professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering the University of California Berkeley, in an email to Design News.

Questions about lithium-ion also prompted Airbus to drop plans for using the technology. The company had originally proposed to use it on its A350 airliner, but opted out after the Boeing incidents, according to several news reports.

Boeing acknowledged that its engineers still don't know the reason for the fire at Boston's Logan Airport, despite lengthy analyses by the National Transportation Safety Board.

"In the events of Logan and Takamatsu, we may never get to the single root cause," Sinnett said. "But the process we used to understand what improvements can be made is the most robust process we've ever followed in improving a part in our history."

Related posts:

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like