3D Printing Needs to Open Up

May 19, 2014

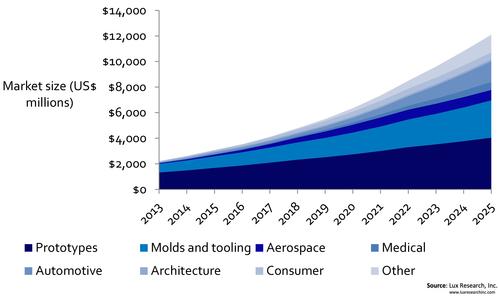

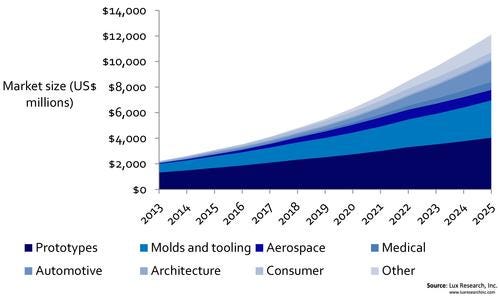

As the 3D printing industry begins a steady shift toward end-production parts manufacturing, some of the prototyping-based models it has operated on for 30 years must change, says a new report from Lux Research titled, "How 3D Printing Adds Up: Emerging Materials, Processes, Applications, and Business Models." Emerging third-party suppliers of materials, design tools, and machines are already challenging those models.

Design News readers following this subject know that most of the media still focus on consumer uses, such as custom jewelry, toys, clothes, food, and guns. But that's not where the technology is making the biggest difference, Anthony Vicari, Lux research associate and lead author of the study, tells us. "Industrial uses, from molds and tooling to production parts, are having a bigger impact."

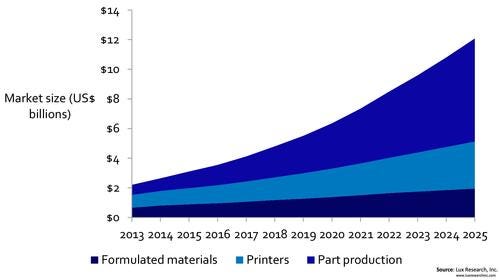

The market for production parts, and the overall market itself, are growing faster than Vicari and his team expected. Last year, they projected a total market value of $8.4 billion by 2025, but this year that 2025 estimate has changed to $12 billion. More than 50% of that total, or $7 billion, will be in production parts, up from 13% today. Printers will be worth $3.2 billion, and formulated materials will be $2 billion.

But to reach those levels, some major changes in processing and printable materials technology must occur, says Vicari. Most third-party materials suppliers are selling directly to end-users, which is easier to do in the consumer space than the industrial space. There, the "razor/blade" model of the big suppliers such as 3D Systems, Stratasys, and EOS has prevailed, where industrial users purchase both machines and materials for those machines from a single manufacturer. Because of that model users pay premium prices for proprietary formulated materials: a markup between 10 times and 100 times. Of the top four manufacturers, which together hold a 31% market share for printers, Arcam alone has an open-materials supply model.

With no open-materials market in the industrial space, users also can't be sure of the material's exact contents. "In the consumer space, it's easy to find out what's in a material, including additives: Their makers are very upfront about it," he continues. "That's because users need to know what recipe to use in each of a hundred different printers. On the industrial side, a 3D printer maker may tell you the material is nylon or ULTEM, but you don't know what else has been added." That's a good model for prototyping -- everything works together out of the box -- but for making end-production parts, no one company has a wide enough range of materials to meet all users' needs. The razor/blade model also makes it very difficult for new industrial materials suppliers to enter the market. The big printer companies are still trying to maintain control, but they risk shutting themselves out of that growth of end part production, he says.

Even so, the report says there's a growing number of independent materials suppliers, including Raymor Industries, Taulman 3D, MadeSolid, and Ceralink that offer high potential.

The razor/blade model also inhibits the use of 3D printing for end-production. For example, it makes it difficult to adapt 3D printing for in-house manufacturing if you're using proprietary machines, but can't tweak the process to adapt it to your needs. "If you don't know the process, you can get significant variations from one run to the next," says Vicari. "How do you how ensure consistency from the printer and its materials, and make them more reliable? What has to be different from QC? What recipes should get what properties? How do you confirm the process is reliable?" This is especially important in aerospace and medical, the two industries at the leading edge of end-parts production, which are highly regulated.

One of the promises of 3D printing has been the ability to produce end-parts locally, with lower startup costs. Now that low-cost printers are getting more technically advanced and competing with low-end machines from the big suppliers, there will be cases where it makes sense to go with the smaller one if it has an open-materials model, he says. Meanwhile, the expiration of yet more patents will continue to trigger growth. Several years ago, the expiration of some early patents for filament fusion machines patented by Stratasys as FDM (fused deposition modeling) began fueling an explosion in the low end. Over the next three years an even bigger shift is coming as patents on other key 3D printing technologies, such as SLS (selective laser sintering), start expiring. This will lower the costs of those methods and widen the range of capabilities that are available to users.

Related posts:

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)