December 3, 2015

Even as the popularity of light-emitting diode (LED) lighting grows, the vast majority of end users still have simple needs. Turn it on, turn it off; light and dark. Nothing fancy.

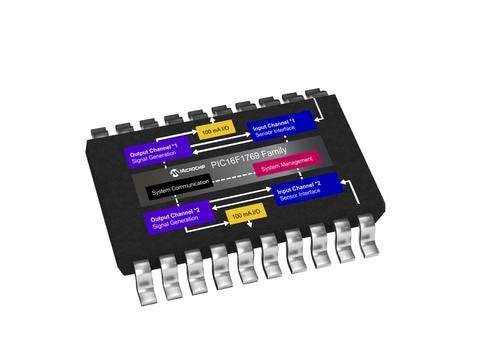

But that's changing, and the change is coming fast. LED lighting systems need to be intelligent and efficient. "Being able to adjust the light -- not only the brightness but the color -- is very important," noted Steve Kennelly, senior manager for lighting and medical at Microchip Technology Inc. "Customers also want networking, so the lights can talk to each other."

This is happening everywhere, in cameras, refrigerators, streetlights, and machine vision systems. In medical, physicians, for example, want to raise and lower the illumination or even change colors in examination rooms and operating rooms. Automakers want to be able to tweak the colors of their vehicle interior lighting. And they want smart headlights.

Beyond on and off

Only electronic lighting can make satisfy these needs, and "you need intelligent control," Kennelly said. That's why project engineers are looking to a new breed of LED drivers.

To appreciate why LED drivers are important, however, it's first necessary to understand what they do. At their simplest, they're a lot like ballasts in fluorescent lights, reconfiguring the input current and voltage to drive the LED chip. In analog lighting, a printed circuit board with a power conversion section containing oscillators and inductors and an integrated circuit tell the components what to do.

Of course, some LED drivers do little more than on-off switching. "The predominant number of cars using LED headlights are not doing anything fancy," said Bryan Legates, director of design engineering for power products at Linear Technology Corp. "It's just a high beam and a low beam and it works like the old halogen or incandescent bulb."

But today's LED drivers can do much more than that if required. Texas Instruments' (TI) LM3466 LED driver, for example, enables strings of LEDs to "talk" to each other. By doing so, it can balance the current between the strings, even when there's a fault or one string is shorted.

"It's trying to make sure that no matter what happens to the parallel LED strings, the current ratio between them is always identical," said John Perry, marketing manager for TI's Lighting and Power Products Business. "So if you have a constant source of 1A, and you drop from four strings to three, it rebalances the current so each string gets 333 mA, instead of 250 mA."

For many LED users, the main goal is to have good current regulation over time. In automated factories, for example, LEDs are being applied in conjunction with machine vision systems. To make sure these systems can always read the markings on parts, users employ drivers that can precisely control the current of the nearby light sources. Linear Technology offers a variety of such drivers, including the LT3763, LT3744 and LT3791, to do such tasks. "The customers want good current regulation, so that once they calibrate the light source, it stays the same over a long lifetime," Legates said.

In some cases, however, the new breed of drivers is enabling LEDs to do things that couldn't have been done previously. A case in point is the "matrix headlight," which enables the vehicle to work with sensors to "see" oncoming traffic and then dim the brights so as not to blind drivers. The key is that it does so selectively, dimming specific blinding LEDs while maintaining the light on the roadway.

"Many of the newer vehicles already have the sensors and the information needed to make that happen," Legates said. "Now they're just feeding it to the headlamps."

Such "smart headlights" have existed, but they were electromechanical. LEDs and LED drivers, such as Linear Technology's LT3965, eliminate the need for the complicated arrays of actuators for steering the incandescent beam away from the oncoming driver. "In the past, automakers used halogen lights and motors, but they couldn't change the light shape as quickly and ended up with a very complicated system that didn't work as well," Legates remarked.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like