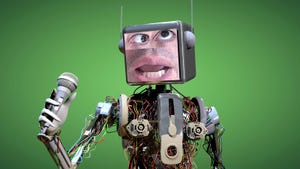

Telephones have made enormous progress over the past century and half.

Electronics

The Telephone’s Long and Storied HistoryThe Telephone’s Long and Storied History

Trace the developments in telephones from Alexander Graham Bell to today’s smartphones.

Sign up for the Design News Daily newsletter.

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)