Thanks to a number of factors, desktop 3D printing is finally moving out of makers' basements and into professional offices and factories.

February 8, 2018

We've all seen the results of desktop 3D printing. And let's be honest, the results have often been less than impressive. Things like homemade toys and models have a certain cool factor, but once that wears off you have to ask yourself, is a desktop 3D printer just a $3,000 tchotchke maker?

That's not to discount however the things being done by makers and the DIY movement. Armed with a 3D printer and a Raspberry Pi, a creative hobbyist can make all sorts of gadgets. But the question for the 3D printing community at large, as well as printer manufacturers, is how can desktop 3D printing move out of the hobbyist realm and deliver on its promise of becoming a professional tool as ubiquitous as a desktop PC?

|

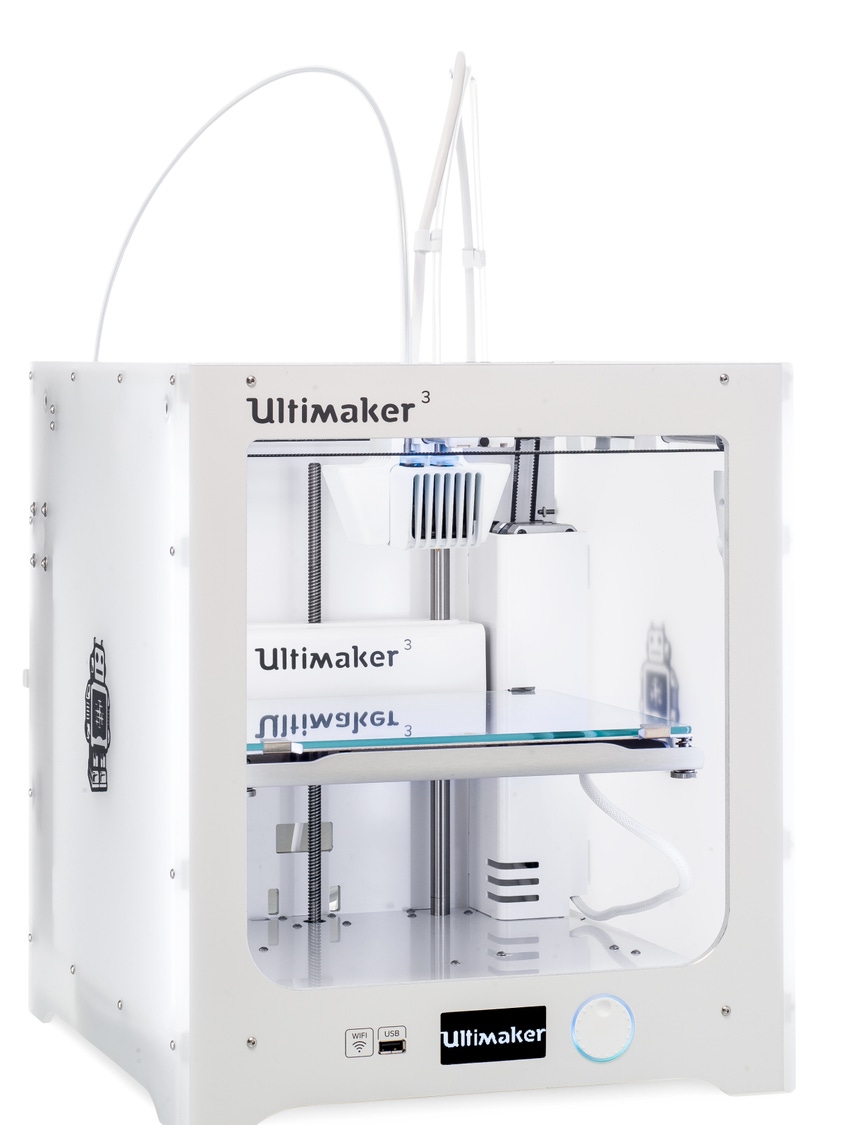

Thanks to lower costs, quality, and a push from the open source community desktop 3D printers like the ones from Ultimaker are moving into manufacturing spaces. (Image source: Ultimaker) |

“For years, even 10 to 20 years ago, we've talked about a 3D printer on every engineer's desk. But it's becoming more and more reality. When [desktop 3D printers] started they were for makers,” John Kawola, President at Ultimaker North America, a manufacturer of desktop 3D printers, said. Speaking to an audience at the 2018 Pacific Design & Manufacturing Show, Kawola said the issue with early desktop 3D printers was, frankly, they didn't work particularly well. “But makers love that because they want to fix things. ... There are online forums with thousands of people getting on at night trying to get their printers to work.”

The upside to all of this Kawola said, is that many makers are engineers in their day jobs. And this open-source community that has sprung up around 3D printing hardware, software, and materials is creating a natural ecosystem that is moving desktop 3D printing into offices and factories.

In the material space alone, for example, Kawola pointed to how it was once only possible to 3D print with PLA. Today users have choices between ABS, CPE, TPU, Nylon, and even metals.

“I credit that to the open-source nature of desktop 3D printing,” he said. “The customers now have a range of materials they can use. There are now hundreds, maybe thousands, of entities developing filaments for desktop 3D printing. That wasn't true two to three years ago and it's part of why desktop 3D printing is becoming more useful in a professional environment.”

Kawola called it a “convergence of capability” that is creating this shift. In the past the quality of 3D printing hasn't been great from a professional standpoint, with plastic prints that didn't really meet high-end requirements. But now the reliability of the hardware, mechanics, and software are changing all of that. “Software has gotten more reliable and consistent,” Kawola said. “Part of it is due to open source -- people contributing and making software better.”

While the killer app for 3D printing might always be rapid prototyping, Kawola told the audience that consumable parts are a key area in which desktop 3D printing is penetrating the factory and office. ABB Robotics, for example, is using desktop 3D printers from Ultimaker to make grippers for its flagship robot, YuMi.

“[The grippers] break all the time, people lose them, they get stolen – it's a consumable item in factories,” Kawola said. “In the past you'd machine these, and you might set up the robot, and it might not quite work, and you'd modify [the gripper] slighty...that takes days or weeks.” With 3D printing ABB has been able to reduce a machining process that could take weeks down to a few hours. Kawola said ABB is now putting a 3D printer with each of its robots to replace consumable parts like these.

Automaker Volkswagen Autoeuropa is achieving similar results by using desktop 3D printers to replace jigs, fixtures, and tools on the automotive production line. “Using outside contractors to machine these parts was too expensive,” Kawola said, noting that loss of these parts could result in auto manufacturers having to stop their production line entirely. “If you have to stop an automotive production line, people get fired.” Since validating the process in 2014, Volkswagen Autoeuropa now produces 93% of its externally manufactured tools in-house – at a significant cost savings to the company.

“We belive there's lots of great new tech and capablites, but the biggest disruption thats enabling this technology to move into manufacturing is cost,” Kawola said. “Take HP for example. They entered the market printing with Nylon. The quality of the parts wasn't that different from what other solutions were offering at the time. The difference is that it's now a lot less expensive.”

He continued, “At a $3,000 price point for a quality printer and the low cost of materials now, customers are saying, 'Let's try that.' They're not sure if it'll work, but it's such a low cost they try it anyway, and if it works they win.”

Chris Wiltz is a Senior Editor at Design News, covering emerging technologies including AI, VR/AR, and robotics.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like