June 5, 2015

![Go Fail in the Real World: Google[x]'s Advice to Engineers Go Fail in the Real World: Google[x]'s Advice to Engineers](https://eu-images.contentstack.com/v3/assets/blt0bbd1b20253587c0/blt557b02ef88b23ffc/653fb09248009d040a68ee53/AstroTeller_GoogleIO.png?width=850&auto=webp&quality=95&format=jpg&disable=upscale)

What do all of Google[x]'s high-profile projects have in common? They all come from a mindset that any engineer can emulate.

How do you create self-driving cars, contact lenses that read glucose, and drones that deliver packages right to your home? If you're Dr. Astro Teller who oversees Google[x], the answer is to get out into the real world and fail as quickly as you can.

Google[x] is Google's "moonshot factory" responsible for the search giant's most ambitious projects. It's the group that brought us Google Glass and is putting fully automated cars on the streets. Speaking at the Google I/O conference last month, Teller told the audience that you don't have to be a tech giant to bring ambitious, seemingly impossible projects to light. "The truth is we can all work on moonshots," Teller said. "Working on things that aspire to be 10 times better rather than 10% better is a mindset."

For Teller, key to that mindset is a willingness to start over from scratch and build new ideas from the ground up. "When you aspire to make the world that much better you have to start over," he told the audience. "You have to acknowledge that what you start next can't come from what happened before."

MORE FROM DESIGN NEWS: Babak Parviz Goes Through the Glass

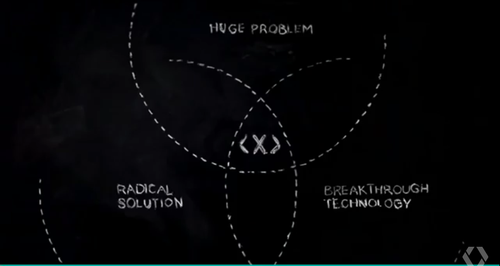

Google's moonshot blueprint comes from the intersection of a huge problem, radical solution, and a breakthrough technology -- tempered with some good business sense. "Each project that fits into this mold then has to describe how, in principle, it could produce a Google scale business or value to the company in order for us to help it move forward," Teller reminded the audience. "Our goal is to have each of these things create a ton of value to the world but also create a fair equitable return on investment for taking these big risks."

How do you arrive at the radical proposal of autonomous vehicles for example? "1.2 million people die every year in car accidents and more than a trillion dollars is wasted every year with people sitting in traffic." Teller said. Factor in breakthrough technology coming from DARPA and advancements in sensor technology and the total vision begins to take shape.

Once these conditions have been met, Google[x]'s core operating principle is "throwing ourselves out into the world to get contact with the real world as fast as possible," Teller said. "It's not a natural thing but it is critical." When taking on huge, difficult projects it can be impossible to know the right thing to do right out of the box. But what you can do is have a process by which you can realize if you're on the wrong track as quickly as possible. Teller encouraged engineers to ask themselves, "How and how fast can you discover that what you're working on is the wrong thing to be working on?" Admittedly, it can be a painful process for all involved, but learning you're wrong quickly can be much less painful in the short term than farther down the road.

Real World Demand

Teller cited Project Wing, Google[x]'s program for creating delivery drones, as a prime example of Gogole's failing principle in action. The initial idea for the project was to deliver automated external defibrillators (AEDs) to the point of care in emergency situations. Again, you have the huge problem, radical solution, breakthrough technology intersection -- emergency response times can cost lives and drones present both a radical solution and breakthrough technology for solving this.

But what sounded great on paper didn't apply so well to the real world. "We had engineers start building a first version of the vehicle ... also, we immediately had a real-world team go out to ask, 'Can we kill this project right now? Is something wrong with the plan?'" Teller said.

After talking with emergency responders and people who ran 911 centers, Google[x] quickly discovered several obstacles. First, AEDs are difficult to use and the drones would essentially be flying a device to people they wouldn't be able to quickly figure out. Also, the team discovered that 911's infrastructure isn't really set up in a way that would allow drones to be immediately deployed to wherever an emergency call is coming from.

"So the team came up with a new beachhead," Teller said. "Let's just throw ourselves in the world." When Google[x] started doing drone deliveries in Australia in 2014 they were able to more organically determine what things people really wanted delivered -- finding demand that was already there rather than trying to force it. They discovered that cattle ranchers, for example, wanted vaccines delivered. "We would never have figured that out in a conference room." Teller said.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like