Imagine a sensor that can be mounted behind, or embedded in, a control surface, providing the functionality of pushbutton or toggle switches without the bounce.

February 7, 2022

I’ve been cogitating and ruminating about a mixed bag of things recently, but mostly to do with the way in which we control our electronic systems. In some ways, we seem to be incredibly advanced. My wife (Gina the Gorgeous) and I decided to treat ourselves to a 65-inch 4K ultra-high definition (UHD) Insignia TV for Christmas. This is something that would have cost thousands of dollars just a few short years ago but was only a few hundred dollars in the pre-Christmas sale.

The picture alone makes me gasp in awe. When I was a lad growing up in the 1960s, we had a black-and-white cathode ray tube (CRT) TV whose screen was probably only around 18-inches (if I ever get my time machine working, I’ll go back and measure it). The thought of having a color television never struck my young mind. It simply never occurred to me that there would ever be such a thing as a color television, let alone something classed as ultra-high definition.

Similarly, the idea of having a remote device to control the television was not something I ever considered. Of course, we had only two or three television channels in those days of yore. Still and all, even if I had known that remote controls were “a thing,” there’s no chance my parents would have splashed the cash for one. I can easily imagine the response had I asked for such an extravagance: “What? You are too lazy to walk across the room and change the channel?”

In turn, this reminds me that the first wireless remote control looked like something inspired by The Jetsons. I am, of course, talking about the Zenith “Flash-Matic,” which first made an appearance in 1955. The idea was that there were four photoelectric cells mounted around the four corners of the screen. The lucky owner used a space-age-looking flashlight to shine a beam of light onto the appropriate photocell to activate the desired function: volume up, volume down, channel up, and channel down.

If only my dear old dad could see me now. Not only do I have a television of a size that would have dominated our small family room in England – and a color television at that – and not only do I have access to hundreds of channels, some of which are actually worth watching, but I also have a remote control that is elegant in its simplicity. What would have really blown my dad’s socks off is to discover that I can talk to my remote control to locate whatever it is I’m interested in watching. I can imagine him shaking his head in disbelief.

I also remember when I first came to live in America in 1990. I purchased my first house in 1992. It had a garage door opener. I couldn’t have been more excited if I tried. We had garage door openers in England of course, but only for the rich and famous. No one I personally knew owned such awesome technology. I used to look forward to returning from work in the evening so I could use my garage door opener. I’d sit in my car in the drive with a great big smile plastered across my face (I’m easily entertained). And, once again, I could imagine my family and friends back home saying: “What? You are too lazy to get out of your car and open the garage door by hand?”

The really funny thing is that there’s nothing new under the sun, as they say. For example, the control systems most of us use on a daily basis are pushbutton switches and toggle switches. The basic form of pushbutton switch we use today first made an appearance circa 1880, while the toggle switches that we know and love first appeared on the scene circa 1916. I was recently reading an article, At the Interface: The Case of the Electric Push Button, 1880-1923, by media studies scholar Rachel Plotnick. In this piece, Rachel notes that, as early as 1916, an educational reformer and social activist called Dorothy Canfield Fisher warned: “There is a great danger of coming to rely so entirely on the electric button and its slaves that the wheels of initiative will be broken, or at least become rusty from long disuse.” Thank goodness Dorothy never got to see a TV controller or a garage door opener.

A few months ago, I wrote a column about switches here on Design News: How to Keep a Flipped Switch from Bouncing Like a Golf Ball Dropped from the Roof. The thing is that switches bounce. That’s what they do. This is true of toggle switches, pushbutton switches, micro switches, limit switches... just about every switch on the planet, apart from things like mercury tilt switches, with which most of us will never come into contact (no pun intended).

So, when you stop to think about all of the amazing electronic gadgets that surround us – including the spiffy remote control for my new television – doesn’t it strike you as being a little strange that these devices employ pushbutton and toggle switch technology that’s fundamentally more than 100 years old?

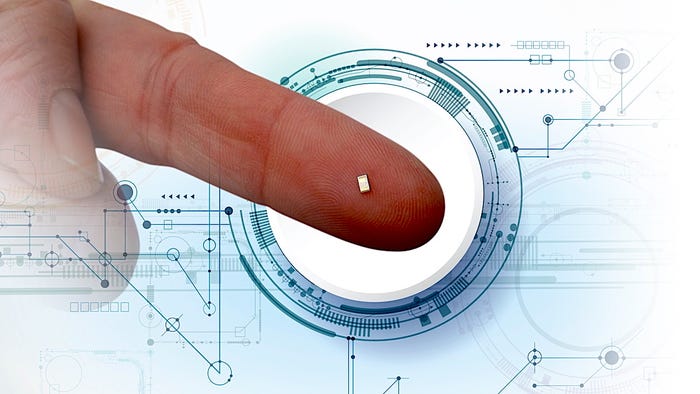

Happily, there may be a solution on the horizon. I was recently talking to the guys and gals at a company called UltraSense Systems. These little scamps have developed a teeny-tiny ultrasonic sensor called the TouchPoint Z beside which a grain of rice would look crude and clunky.

The ultrasonic transducer in the TouchPoint Z is powerful enough to penetrate up to 5 mm of hard plastic or 2 mm of stainless steel, which means this sensor can be mounted behind, or embedded in, the control surface of your choice.

Of course, there are other ultrasonic sensors available, so what makes this one different? Well, how about the fact that it also boasts four minuscule piezo strain gauges that can detect deformations as small as 100 nm. It also includes a microcontroller that can report everything back to a host system via a 2-wire I2C or UART interface.

The ultrasonic transducer can detect the presence of a finger, while the strain gauges can detect the amount of pressure being applied. The fact that you can mount these sensors in or behind the control surface – whose functions could be indicated via embedded LEDs and suchlike – results in aesthetically pleasing interfaces that are immune to things like water and contaminants. The bottom line is that these bodacious beauties can provide all the functionality of pushbutton and toggle switches, but without the hint of a whiff of a sniff of a bounce. Truly a switch for the 21st Century! What say you? Are you as excited by all this as am I?

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like