University of Illinois professor Paul Braun has developed a battery structure that offers high power without sacrificing energy.

August 24, 2011

One maxim of electric car battery design is that energy and power are a tradeoff. Boost the energy, and you lose power, and vice versa.

Now, though, a professor at the University of Illinois has developed a battery structure that changes all that, and he hopes to have it in production applications within three years. Paul Braun, a professor of material science, says his structure could enable users to boost energy without sacrificing power.

"Our system is particularly good at producing high peak power -- anywhere from 10 to 100 times greater than the power of a conventional rechargeable battery," he told me. "For systems where you want a lot of power relative to the size of the battery, there's a definite advantage."

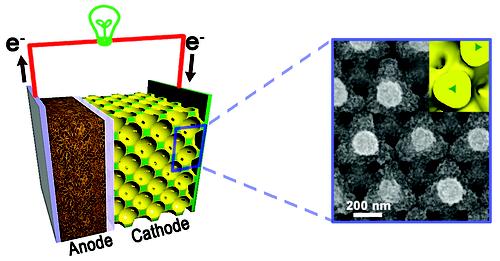

The technological advance is in the physical structure, not the chemistry, and Braun has applied it to both lithium-ion and nickel-metal hydride batteries. The key is a new thin film that can be wrapped into a three-dimensional foam structure. The 3-D structure achieves high active volume (which translates to high capacity) and large current. As a result, it offers fast charging and discharging.

"The open nature of the foam promotes efficient ion transfer," says Braun, who just launched a startup called Xerion Advanced Battery Corp. "That's why we achieve a high rate."

He is refreshingly careful about not overstating the battery's potential applications. Conventional hybrids and very mild hybrids with start-stop capabilities are the most logical candidates in the auto industry, he says. Today, those vehicles typically have smaller batteries that aren't particularly good at providing extra power for propulsion. "Our high power capability is much more important in conventional hybrids, where you're trying to recover energy from the brakes and use it for propulsion."

Braun's three-dimensional open foam structure promotes efficient ion transfer, which translates to greater power and faster recharge times.

The battery structure is less likely to see action in electric vehicles, which typically have big batteries that can provide enough power by virtue of their size. One of the battery's prime advantages -- faster recharging time -- is not yet applicable for pure electric cars, because of a lack of electrical infrastructure, Braun says.

"If we want to charge in an amount of time that's similar to filling a car with gasoline, it's just not going to be possible today," he says. "Gas stations don't have the necessary power feeds coming into them. It's going to require partnerships between power utilities and whoever builds the stations."

Braun also says the 440V architectures used in today's fast recharge systems might not be sufficient. Rechargers might need higher voltage, multiple lines, or even large contact plates under the car that could serve as charging receptacles. "This is something that the utility companies and automakers haven't even speculated about, because the right battery hasn't existed."

The quick recharge capabilities do matter for makers of consumer electronics. Braun and his new company are already talking to manufacturers of cellphones, laptops, hand power tools, and military systems. In those applications, infrastructure won't matter. Today's 110V wall sockets are sufficient to charge a phone in less than a minute, and a laptop in a couple of minutes, if they employ Braun's battery, he says.

"We think the idea of being able to pop up to a charging station and being ready to go a minute later is pretty attractive," Braun says.

As the new company rolls out its test batteries, interest has been high in both automotive and consumer electronics. The fact that the battery's energy density remains high while it doles out high levels of power is attractive to OEMs, Braun says. "That's where we can help. What we really offer is lots of juice."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like