August 18, 2011

As mechanical engineers move closer to the embedded processing realm, complex technologies such as field programmable gate arrays (FPGA) could pose minor accessibility roadblocks. Or maybe major ones.

"We have our own software, but it appeals to a different set of people," Harry Jason Raftopoulos, director of the industrial scientific and medical segments for Xilinx Inc., a maker of FPGAs, told me. "Our software appeals to the people who actually design the board, or who make the chips communicate. These are EEs (electrical engineers), not MEs (mechanical engineers)."

Increasingly, manufacturers such as Xilinx know they have to change that. As the line between electrical and mechanical engineers blurs, the MEs are starting to get more involved in the design of embedded technology, including medical imaging systems, automotive displays, and speech recognition, as well as defense and aerospace applications.

FPGAs can help in those applications for a couple of reasons: they provide design flexibility and faster time-to-market.

The problem, however, is that the expertise of mechanical engineers typically lies in their domains -- be it medical systems, automobiles, or myriad other technical areas. Their expertise doesn't reside in microcontrollers, software, or FPGAs. The same holds true for other "domain experts" -- such as manufacturers, or even doctors and dentists, who have electronic-based ideas they want to implement in their professions.

"The domain people have a giant need for FPGAs, but they just don't have the background that's needed," Jamie Brettle, partner development manager and product manager for embedded software at National Instruments Corp., told me.

The good news is that companies such as National Instruments and Xilinx are working on ways to make FPGAs more accessible to the so-called domain experts. Nearly a decade ago, Xilinx embedded its software tools in NI's well-known LabVIEW, a graphically-based virtual instrumentation program. The result is a graphical environment module known as LabVIEW FPGA, which enables domain experts to program FPGAs with block diagrams. The block diagram methodology uses automated code generation techniques and is said to be more intuitive than traditional programming methods.

"It provides a level of abstraction that allows you to think like a human being," Raftopoulos says. "It allows you to think in blocks, and in terms of top-down design, so you can design your own embedded system without worrying about the intricacies of the programming language."

The idea is to be able to combine FPGAs with commercial off-the-shelf hardware to create FPGA-based control systems. Xilinx says the technology has been used to build industrial robots, intelligent security cameras, and driver assistance systems that help spot road signs and reduce accidents for drivers.

At the NIWeek technical conference a few weeks ago, Xilinx added another dimension to the FPGA equation. A crossover platform called Zynq now combines the software programmability of an embedded processor with the hardware flexibility of an FPGA, giving domain experts another tool to help push the bounds of embedded systems.

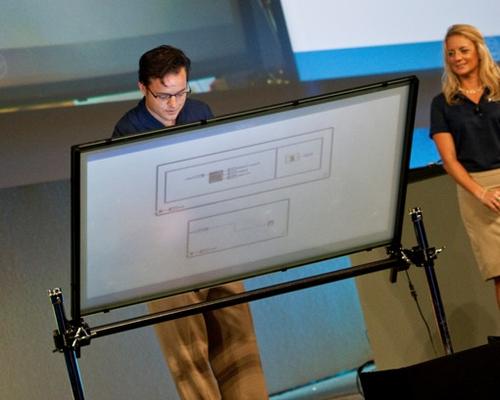

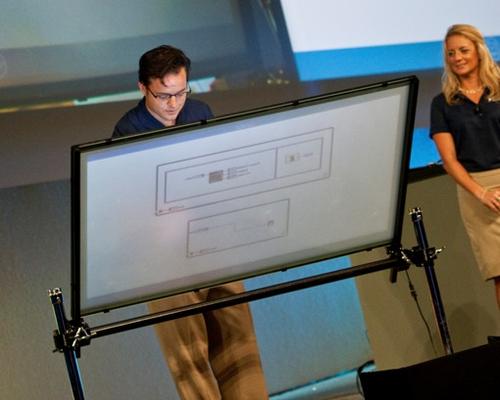

At the conference, NI engineers showed how Zynq is being employed in the creation of a next-generation multi-touch editor. The multi-touch editor, which runs on a Windows 7 platform and projects onto a 55-inch frosted glass display, uses optical sensors to enable designers to manipulate figures on its glass surface. During a demonstration, NI engineers used the device to prototype the architecture for an electric car-charging system.

"When you combine this functionality with the LabVIEW design environment, great things will happen," Vin Ratford, Xilinx's senior vice president for worldwide marketing and business development, told the conference audience.

The bottom line is that software and hardware suppliers are attempting to step in and make FPGA technology accessible to a broader audience, even as the technology keeps advancing in giant leaps. That's important because FPGAs are a useful tool for embedded systems designers. Their programmability can enable engineers to make changes to their products as they step through the design process, and they can eliminate the need for designers to know everything about their embedded system when they launch their idea.

"Eventually, a mechanical engineer can attain the level of knowledge and expertise that's needed for them to use FPGAs," Raftopoulos says. "We're just trying to make it easier."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like