Automotive Engineering

More Topics

2025 Porsche Taycan

Automotive Engineering

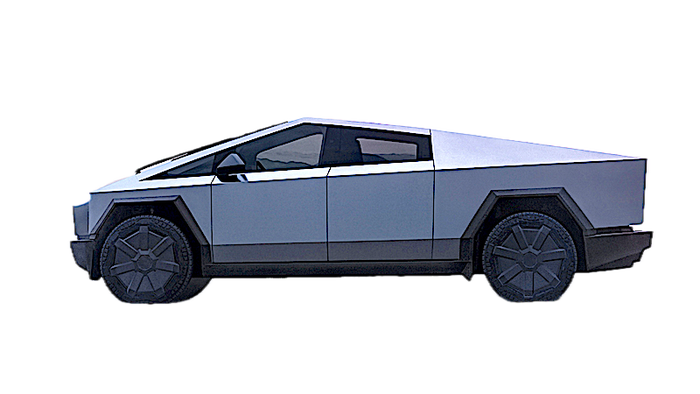

Amsted’s 2-Speed EV Transmission Boosts Range 10 PercentAmsted’s 2-Speed EV Transmission Boosts Range 10 Percent

Only the Porsche Taycan has used a 2-speed transmission so far, but Amsted’s efficient clutch designs might change that.

Sign up for the Design News Daily newsletter.